The approach to Houghton Hall along the flat Fens, under broad, sweeping, luminous skies, is like coming to the ends of the earth. A Palladian edifice, crowned with cupolas surmounted by gilded weather vanes, dramatically comes into view through avenues of lime trees, where white fallow deer freely roam.

The restrained exterior of honeyed ochre Whitby stone, with its centrepiece of classical statues, betrays little of the sumptuous splendours within.

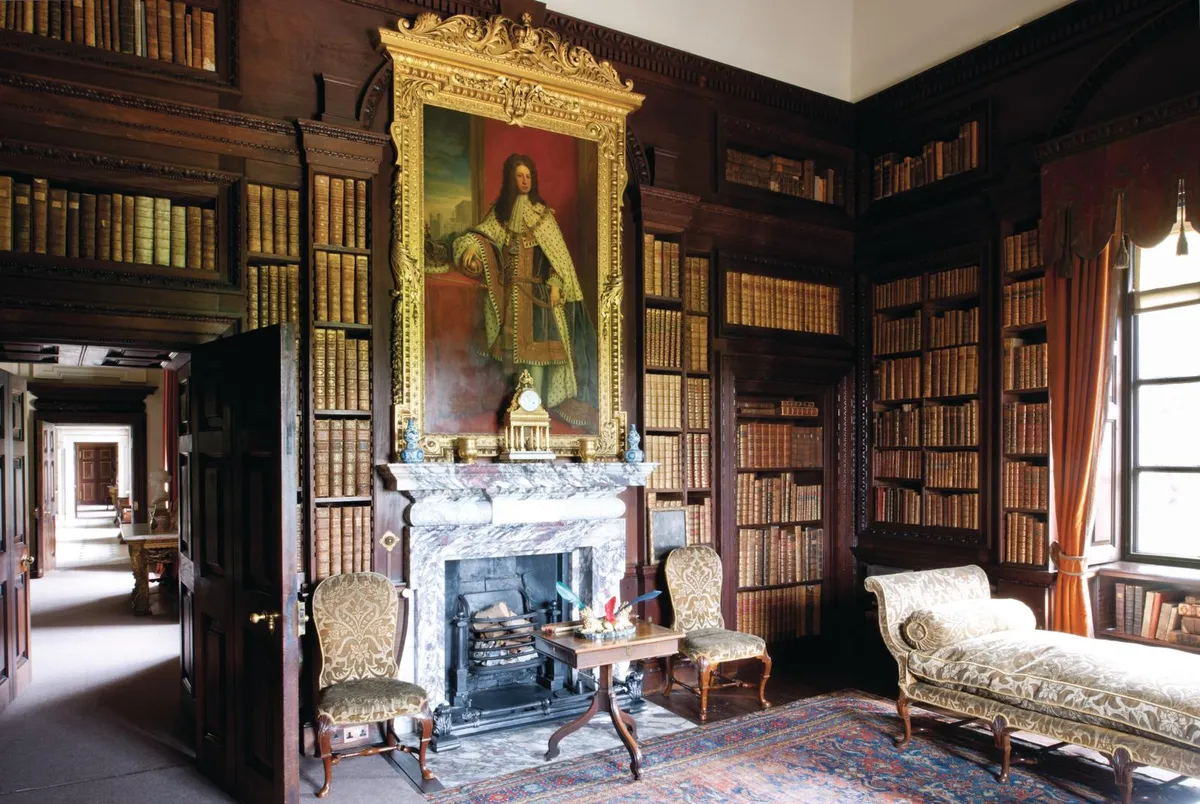

British prime minister Sir Robert Walpole commissioned the house between 1722 and 1735, when England was reaching its zenith in the worlds of art and architecture. Initially, the architect was James Gibbs with the subsequent input of Colen Campbell and Thomas Ripley, while the grand state rooms were lavishly decorated by William Kent.

The three great houses of the Whig ascendancy in Norfolk (Holkham, Raynham and Houghton) all featured William Kent’s designs and Houghton was the first to proclaim the new spirit of British classicism.

Stepping inside, visitors ascend the great staircase, walking past a bronze gladiator (a copy of the c100BC Borghese Gladiator), who raises his shield in a gesture that appears to usher you into the ensuing suite of grand rooms.

Starting with the great Stone Hall, each of the eight state rooms is imbued with themes of classical mythology, presided over by a Roman god – Apollo, Venus, Bacchus or Minerva.

You might also like Inside the real life Downton Abbey: take a tour of Highclere Castle

The Stone Hall does indeed transport you to Ancient Rome. Putti sculptures cling to the pediments, while Kent’s swagged masks hover above antique busts of the Roman emperors. In the great staircase, Kent’s painterly skills excel in the form of oil-gilded grisaille depicting Meleager and Atalanta hunting a wild boar.

Upstairs, the green velvet bedchamber features unusually pristine Flemish tapestries of mythological scenes and the 15ft-high silk velvet and gold embroidery bed, by William Kent, is thought to be one of the finest examples of an 18th-century bed anywhere in the world.

The Picture Gallery includes paintings by Artemisia Gentileschi of Samson and Delilah, a scene from Hamlet by William Orpen and views of Florence by Thomas Patch; while there is a separate gallery space that is used for occasional exhibitions.

With the exception of the Old Masters collection (brought together by Walpole in the 1720s and sold to Catherine the Great of Russia in 1779), the contents of the house have remained intact. This, in part, is thanks to the fact that the house was left to rest for extensive periods.

In 1804 the Cholmondeley family – to whom the house had passed through marriage in 1797 – moved to the newly built Cholmondeley Castle in Cheshire, only returning to Houghton for the hunting season. Then, from 1888, it was rented for 28 years to eight different tenants.

The house only revived in 1915 when the 5th Marquess of Cholmondeley and his wife, Sybil, (née Sassoon), took up residence. Sybil used her inheritance to save the fabric of the house from dry rot and deathwatch beetle.

You might also like Britain’s best stately homes to visit

After the Second World War, Houghton gained an influx of fine 18th-century furniture and paintings from Sir Philip Sassoon, Sybil’s brother. These Sassoon treasures include Isfahan carpets, a pair of gilt gesso mirrors surmounted by squawking hoopoe birds, French small-scale commodes and secretaires.

Although much of Sassoon’s collection had been designed for smaller French interiors, they give a feeling of Parisian elegance. When Sybil opened the house in 1976 to the public, 40,000 people flocked to Houghton within that first year, finding it still steeped in character and atmosphere, untarnished by the 20th century.

Today, Houghton is lived in by the present Marquess, David Cholmondeley and his young family. Like his ancestors, he is a patron of the arts and – perhaps unexpectedly – champions contemporary, abstract works. In 2017, Houghton hosted a six-month exhibition dedicated to the British landscape artist Richard Long.

‘The purity and simplicity of Richard Long’s vision seems the perfect counterpoint to the 18th-century classical landscape of Houghton,’ explains Lord Cholmondeley. ‘His timeless forms seem to hark back to the earlier civilizations that once inhabited this part of Norfolk. We tend to show contemporary art (such as works by James Turrell, Anya Gallaccio and Rachel Whiteread) separately from the house and its historic collections so as not to confuse people. Each sculpture or artwork has its own world so you can walk around the grounds and discover them.’

Indeed, visitors who have found themselves deeply affected by the astounding beauty and opulence inside the house will surely find Houghton’s grounds a soothing counterbalance in the form of the unexpected cool conceptual art within a bucolic setting.

Houghton’s landscape, filled with striking, contemporary artworks, may now be something way beyond that which Sir Robert Walpole initially conceived, but at its heart, the hall and its surroundings remain very much a temple of the arts.

More homes from Homes & Antiques

- An antiques dealer's 18th-century home in London

- A Swedish manor house once home to a King

- A 17th-century home in Gloucestershire

- A 19th-century Scottish home

Sign up to ourweekly newsletterto enjoy more H&A content delivered to your inbox.