Beyond the terrace and ha-ha, three riders trot across parched parkland in hazy sunlight, past a dramatic dead tree in front of a magnificent, seven-bay, late 18th century stone house. A scene from Far From the Madding Crowd, perhaps? No; yet some of the pivotal scenes of the evocative film, starring Carey Mulligan as Bathsheba Everdene, was shot here.

The Verney family’s fine property, Claydon House, doubles as Hardy’s William Boldwood’s mansion. Claydon doesn’t need a Hollywood film to give it glamour though, for its own story is equally dramatic, featuring pirates, skulduggery – and Florence Nightingale.

In 1463, long before the house existed in its current form, the manor of Middle Claydon was bought by Sir Ralph Verney. Here his tenant Roger Giffard built an H-plan brick mansion in which the Giffards lived until 1620, when Sir Edmund Verney redeemed the lease for £4,000 – after his half-brother Francis sold off the Verney family’s actual home and became a Barbary pirate. Edmund, standard-bearer to Charles I, famously had his hand – still nobly clasping the Royal Standard – hacked off in 1642 at the battle of Edgehill. It was the only part of him ever retrieved.

But it was his great, great grandson Ralph (by now the 2nd Earl Verney) who built the Claydon that one visits today. In 1740 Ralph married heiress Mary Herring, and improved and extended the estate. From 1754-68 he built first the stable blocks and the red-brick east wing (where the Verney family now lives) and then the stone house.

Yet what one sees today – a two-storey house with three imposing, 25ft-high double-cube rooms below and three large bedchambers and other rooms above – while impressive, is only part of the story. Ralph wanted to build a sumptuous residence to rival nearby Stowe. As building began, he decided to create an extravagant mirror wing to contain a vast ballroom, connected to the main house by a domed rotunda topped by a gilded pineapple.

You might also like Blenheim Palace: its history, gardens, architects and ties to the Churchill family

The builder the Earl chose was the supremely talented Southwark-based woodcarver, Luke Lightfoot, who had been working on Ralph’s London home. Unfortunately, Lightfoot convinced him that he could do the whole job – to the disgust of the Earl’s architect, Sir Thomas Robinson, who called Lightfoot (perhaps out of jealousy over his carving skills) ‘an ignorant knave with no small spice of madness’. Robinson was partly right, for Lightfoot was not only light-handed, fiddling the building accounts, but also light on construction skills.

In short, though most of the tripartite house did get built, many of the additional parts soon began to fail structurally and would sadly be demolished by Ralph Verney’s eventual heir, Mary, Baroness Fermanagh. Even sadder perhaps, only one party was ever thrown by the 2nd Earl in what should have been the ultimate party house.

But Lightfoot’s existing interiors are, nevertheless, sublime, dazzling, and quite unexpected. Today one enters through a side door into what was the Great Eating Room (now the North Hall), the first of an enfiladed run of large, high entertaining spaces. Each is effusively decorated with what appears to be florid rococo plasterwork, but in the majority of cases is pine, carved in Southwark then installed on site.

In the Eating Room, herons and mythical ho-ho birds almost fly off the walls, and the ceiling bears an armoury of weapons. In the next room, the blue-brocaded saloon, more restrained flourishes are set off by the deep coffered plasterwork ceiling, sculpted by Joseph Rose the Younger. This is where the ball in which William proposes to Bathsheba takes place in the film. Here too is the portrait of Ralph the Standard Bearer (no painting of the 2nd Earl survives).

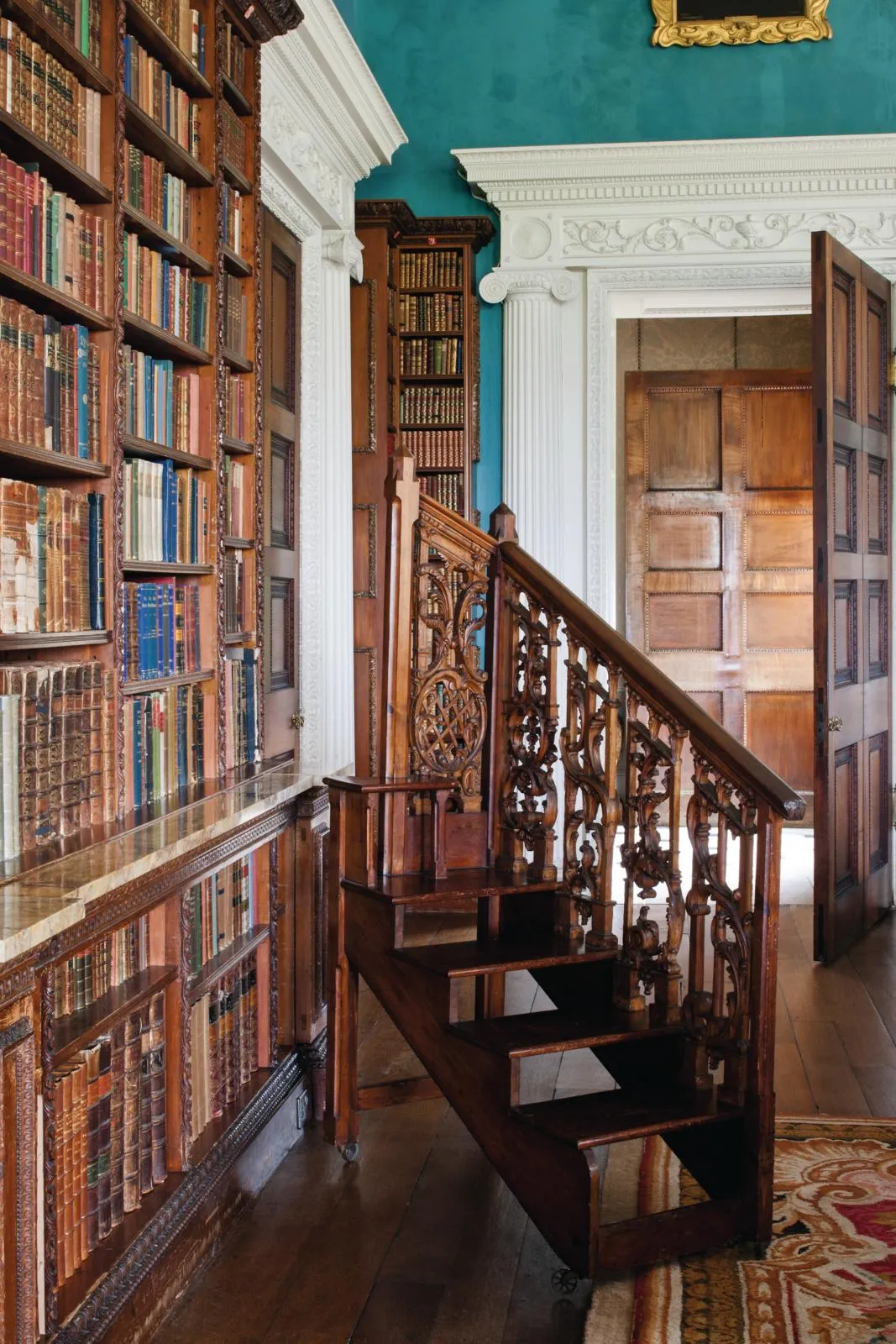

The third room is the library, where William opens the valentine’s card from Bathsheba. It is well stocked with over 4,000 beautiful cased books, and the collection was created and added to by Parthenope Verney in 1860, whose likeness hangs over the marble fireplace. Her younger sister Florence Nightingale stayed several months each year, following her return from the Crimea.

You might also like Inside the real life Downton Abbey: take a tour of Highclere Castle

To reach Florence’s rooms – now restored by the National Trust with a post bed and family furnishings, some of which may have originally been in these rooms – one mounted the so-called Singing Stair in the domed hall.

Conceived by Lightfoot as an important centrepiece, the stair and landing – entirely worked in marquetry and parquetry mahogany, ebony, ivory and boxwood – has a balustrade of black and gold wheat sheaves that tremble and rustle as one mounts, but this is now too frail to use. The surrounding walls rising to the impressive dome carry neoclassical plasterwork plaques by Joseph Rose, who later worked for Robert Adam.

Unusually, the upper floor only has three bedrooms but, with their deeply carved ceilings each with three interior domes, they are striking. Aside from Florence’s apartment, which looks directly out to the 13th-century parish church, the ladies’ sitting room, or Chinese room, is of note.

Here Lightfoot’s imagination ran riot with rocaille figurative Chinese carvings. Even though he had never been to China, he used pattern books to create high-relief work so vivid that it almost springs to life. Also fascinating on this floor is the family museum, full of items collected on the Verney family’s travels.

While Lightfoot may have been a knave, his unparalleled work at Claydon, combined with the house’s story, makes this an absolute wonder, waiting to be explored by the madding crowd.

More homes from Homes & Antiques

- Royal buildings to visit

- Inside Burghley House

- A Lord & Lady's Georgian Mansion in Perthshire

- Inside Burton Constable Hall in East Yorkshire

Sign up to ourweekly newsletterto enjoy more H&A content delivered to your inbox.