What would life have been like if you were employed as a cook-housekeeper or a housemaid and spider brusher in a grand country house, and how different would that existence have been from that of the wife or daughter of its owner?

Erddig, the seat of the Yorke family for nearly 250 years, answers these questions, reaching back in time to offer such an immersive sense of life upstairs and downstairs through the centuries, that it’s been dubbed the Welsh Downton Abbey.

‘What makes it special is that it’s such a complete country house,’ explains Susanne Gronnow, Erddig’s property curator. ‘Upstairs, the interiors are filled with furnishings by some of the finest makers in the 1720s – they were made for the house and are still here, having been nowhere else.’

There are also exquisite ceramics, among them a Delftware vase that came from William of Orange’s palace in the Netherlands via Hampton Court Palace. But it’s the below-stairs collection that really sets the house apart.

‘The servants’ archive is unique in its extent with portraits, poems and documentation that was kept or commissioned by the family,’ Susanne explains. And, yes, however unlikely it may sound, housemaid spider brusher was one of Erddig’s more unusual job titles.

Construction of the house began in the late 17th century. The first owner was Joshua Edisbury, a Denbighshire High Sheriff, whose grand ideas didn’t match his budget. When he went bankrupt, a wealthy lawyer, John Meller, stepped in, enlarging the house and enriching its interiors with opulent silvered chairs, japanned cabinets, Chinese silk, gilded mirrors and tapestries woven by the Soho Manufactory.

Meller died in 1733, unmarried and childless, leaving the house to his nephew, Simon Yorke, the first of an unbroken line (all called either Simon or Philip), who were to inhabit Erddig until it was handed over to the National Trust in 1973.

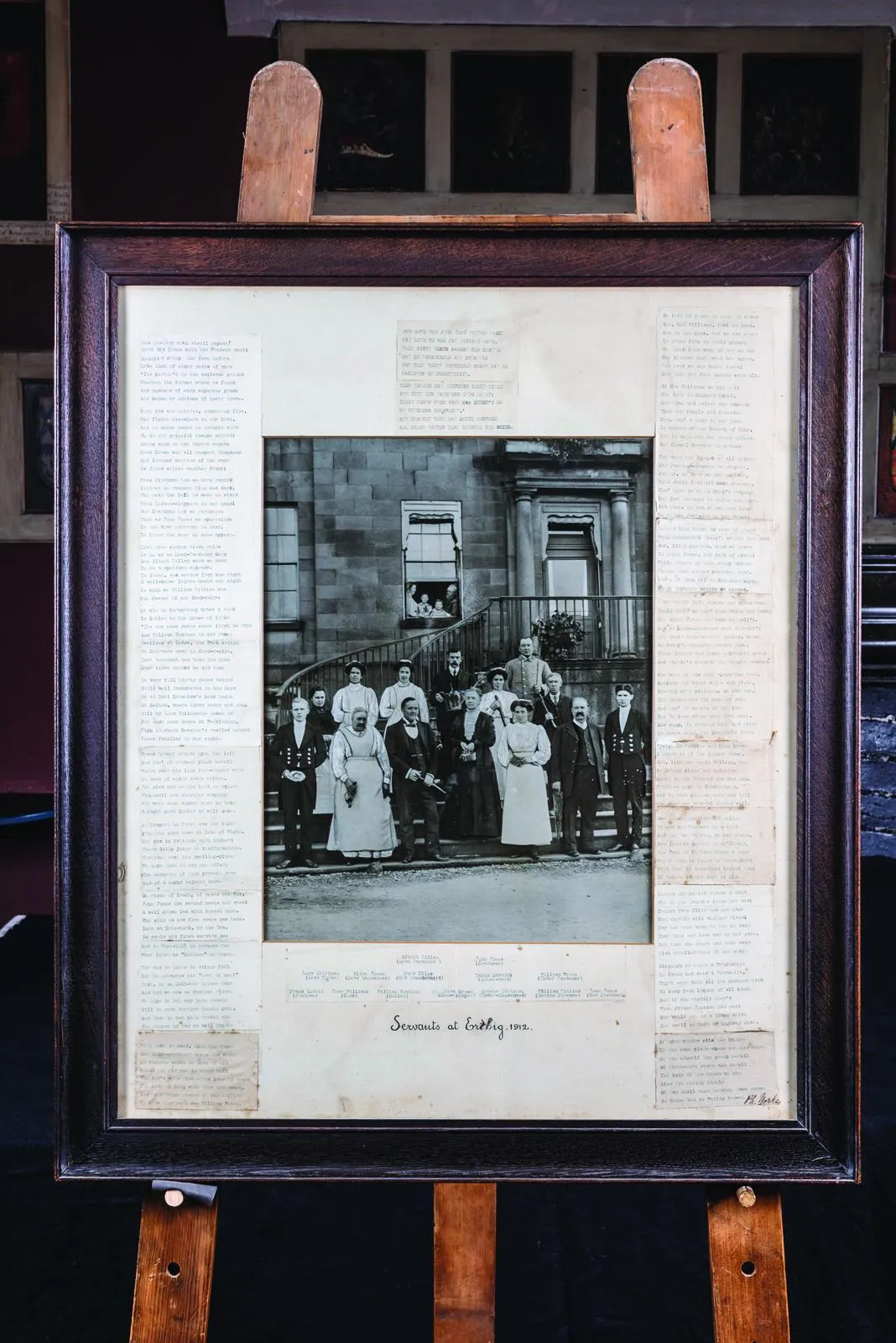

The records of servants’ lives began in the 1790s when Philip I commissioned a series of portraits of his key staff. Seven were hung in the servants’ hall, together with verses about the subjects’ characters and roles. A tradition was thus established and, from then on, paintings, named hatchments and photographs recorded key members of the household. But what was the Yorkes’ motive for this strange tradition, and what did the sitters make of it?

‘It remains unclear,’ says Susanne. ‘Philip was a keen historian, and he may have been recording life in the house for posterity. We don’t know how servants would have seen it, but it was highly unusual to take a likeness of an employee in the 18th century.’ Generations of the same family worked in the house, so a maid from the late 19th century might look up and see a great-grandfather on the wall, which might have provided a sense of stability and connection.

By the Edwardian era, when the last staff were photographed, a dozen or more servants were still employed. The kitchen was the engine room of the house, enabling the comfort of the family upstairs.

In the Yorkes’ opulent interiors, meanwhile, it was a very different world. Mornings might be spent in the east-facing Saloon, the biggest room in the house, writing letters and reading, perhaps sitting on one of John Meller’s silvered, silk upholstered chairs, at the sumptuously inlaid Boulle bureau he had chosen.

High-status visitors slept in the State Bedroom, where the walls are adorned with vividly coloured hand-painted Chinese wallpaper, surrounded by japanned and lacquered furniture, including a 17th-century Chinese coromandel screen.

Music played an important part in the life of the house, and often there were musical entertainments after dinner. ‘Victoria Yorke played to a high standard and her 15-year-old son, Philip Yorke II, bought the Bevington organ in the Music Room.’ The last squire, Philip III, was famous for a less conventional instrument – a joiner’s saw. Locals remember him fondly, playing in local churches, and there’s a saw on display among the instruments in the Music Room.

A wealth of fascinating stories are attached to objects in the collection. One of Susanne’s favourite anecdotes concerns the early 18th-century silvered glass table in the corner of the Tapestry Room. ‘It dates from c1720 and has a mirrored top, painted with Meller’s coat of arms. In the 1850s, when Philip II was aged four, his mother heard the sound of glass smashing and went to investigate.’

She discovered her son trying out a hammer from a box of tools he’d been given for his birthday. The table top still has a crack and will never be replaced. Susanne thinks anyone who has looked after small children will relate to this. Visitors today respond enthusiastically to the atmosphere of the house and such narratives invariably pique their interest, says Susanne.

‘Erddig isn’t overwhelming, it has a nurturing feel. When I tell them the stories there’s often a lightbulb moment. People can imagine living here, and many identify with the servants’ lives.’