The hundreds of blue plaques found on buildings across our capital commemorate the lives of luminaries – from philosophers to pharmacists, singers to suffragettes. But who decides if someone is awarded a plaque, how are they made – and why did a plaque to Karl Marx get destroyed… twice?

What are English Heritage Blue Plaques?

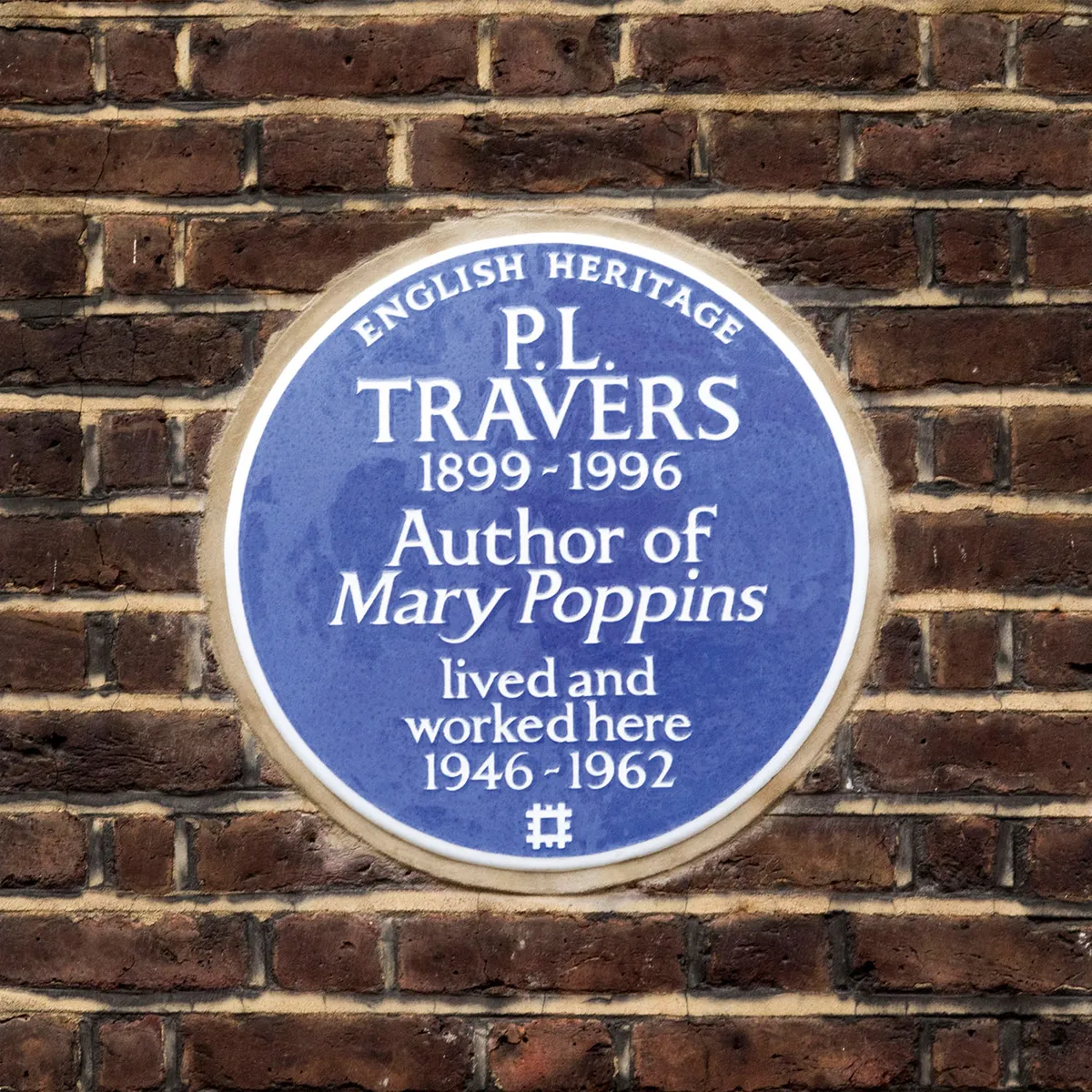

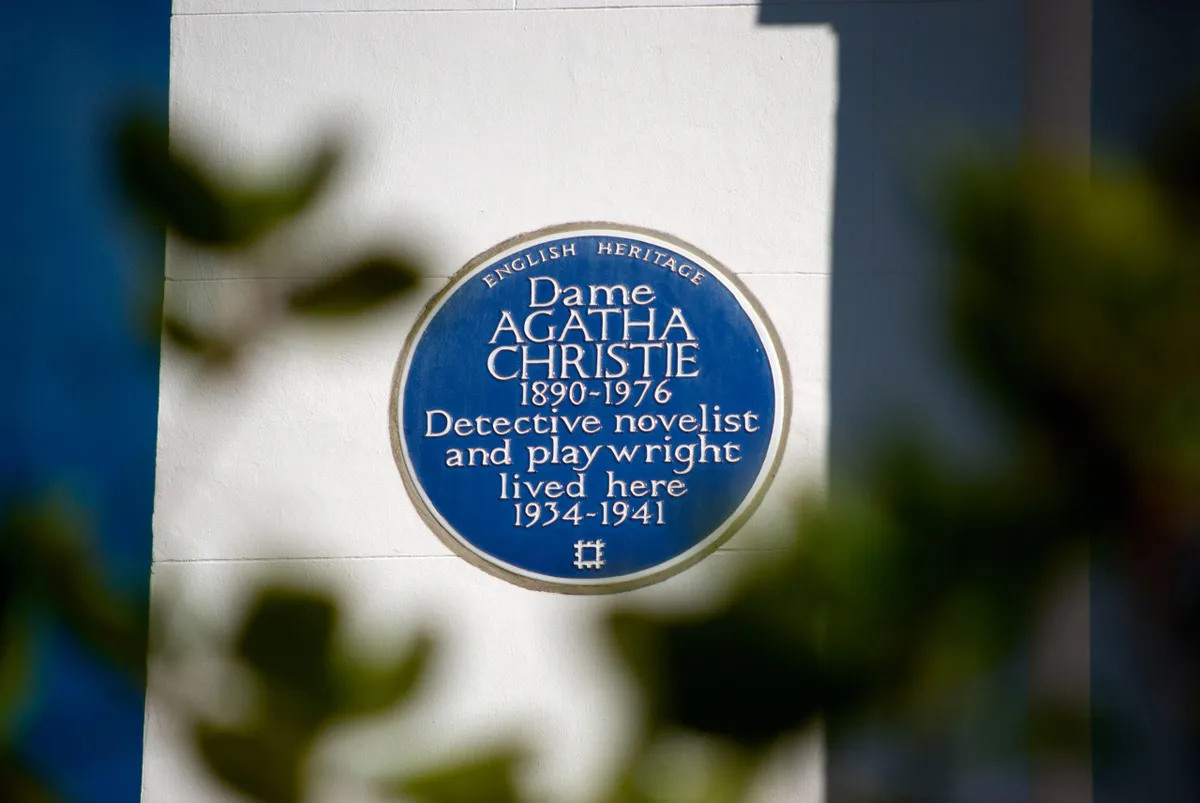

You wouldn’t think there could be much to connect Jimi Hendrix with the chemist and meteorologist Luke Howard, or Oscar Wilde with racing driver Graham Hill. But these notable figures – along with around 950 others – have all been commemorated with blue plaques, the iconic 495mm-diameter discsthat sit on buildings across Greater London in order to bring their historic stories to life for passers-by every day.

The scheme, thought to be the oldest of its type in the world, dates from the 1860s, after the MP William Ewart suggested the idea in the House of Commons.

The Society of Arts took the initiative on in 1866 and installed the first two plaques the following year, to Lord Byron and Napoleon III. The house with Byron’s plaque, his birthplace, was demolished in 1889 but Napoleon III’s plaque survives to this day and can still be seen at 1c King Street, Westminster. Ewart himself has two plaques, in Belgravia and Hampton, which recognise his work as a reformer and backer of public libraries.

How are candidates chosen to receive an English Heritage Blue Plaque in London?

The scheme was operated by London County Council and the Greater London Council but, following the abolition of the GLC, it has been overseen by English Heritage since 1986 and is based entirely on nominations from the public. For a candidate to be eligible for consideration, at least 20 years must have passed since their death, at least one building associated with the figure must survive within Greater London in a form that the person of note would have recognised, and the building in question must be visible from a public highway.

‘We get about 80 valid suggestions a year and we only put up 12 plaques, so it’s pretty stringent,’ says Howard Spencer, senior historian for English Heritage’s blue plaques scheme and the editor of The English Heritage Guide to London’s Blue Plaques.

The English Heritage Guide to London's Blue Plaques, £17.99, English Heritage Shop

A panel of a dozen experts in various fields meets three times a year to create a shortlist from all the nominations. Historically, only a small proportion of the plaques installed under the scheme have represented women and, today, only14 per cent of them celebrate female achievements. Howard says this is for two reasons. ‘Firstly, I think women’s contributions were undervalued. There’s a general historical blindness to the work that they did. The other reason is that, in the past, you didn’t have so many women in the kind of leading roles that would commend them normally for public commemoration.’

In a bid to address this, English Heritage launched a campaign in 2016 to encourage more nominations for women and, for the first time ever, the blue plaques panel is now shortlisting more women than men.

It’s rare that the owner of a building refuses to have a plaque. ‘Usually people see them as an enhancement to their property and they’re happy to have them,’ says Howard. ‘The bigger problem is when we can’t identify the owner or the decision-maker, which happens surprisingly often.

‘We’ve been trying for years to put a plaque up to Henry Fox Talbot, the pioneering photographer, but until his old house changed hands recently, could get no reply to our approaches. All you can do in such cases is go back to it periodically and see whether you have any better luck or whether the ownership has changed.’

How is an English Heritage Blue Plaque made?

When a blue plaque does get the go-ahead, among the first people to hear about it will be artisan ceramicists Sue and Frank Ashworth. The couple – who met while studying at the Royal College of Art – have been making plaques since the early 1980s, first for a scheme run by Lewisham Borough Council and then for the GLC. With their son Justin, they now create all the plaques for English Heritage froma studio in their home near Fowey in Cornwall, as well as taking on private commissions.

Sue explains the intricate process of creating a plaque: ‘It’s a high-fired stoneware,’ she says. ‘It’s cast in a mould and each plaque needs two firings and slow drying – it’s thick enough that you can’t dry it too quickly. People often ask about the glazing. It’s not a Pantone colour, it can differ each time you make up a new batch. And the result is a vibrant surface of character.’

The font was originally designed by Henry Hooper, who was appointed as a designer in the Architect’s Office of London County Council in 1954. ‘He knew that, in order to make plaques, you couldn’t have just a normal Roman font,’ says Sue. ‘He had to modify it so it could be executed in the means of a low relief, which produces a sort of cloisonné effect.’

The whole process of making a plaque is done by hand and can take up to six or seven weeks. Once a plaque has been installed, it’s maintenance-free. They are very slightly domed so that rain and dirt run off them, and will last for as long as the building they’ve been attached to remains standing.

The enduring appeal of the blue plaque is, says Howard, because it draws a link between people and place. ‘It’s a form of public monument that’s very accessible, and it also helps people to become conscious of the historic built environment and hopefully wish to preserve it. It’s eye-catching without being too obtrusive, so I think that’s why it’s become such a successful means of educating people aboutthe past.’

Facts about English Heritage Blue Plaques that you (probably) didn't know

- The earliest plaques, commissioned by the Society of Arts, were made by the pottery firm Minton, Hollins & Co. The encaustic roundels were blue, but this was an expensive colour to produce, so the society subsequently switched to terracotta. Ceramic blue plaques didn’t become the norm until 1921.

- Four blue plaques associated with the London Underground use the font Johnston Sans, which Edward Johnston created for the Tube in 1916 and is still in use today. These include a plaque in Leyton to Harry Beck, who designed the diagrammatic Underground map in 1933, and one to Johnston himself in Chiswick.

- Between 1998 and 2005, English Heritage ran a pilot project to put up plaques in Birmingham, Liverpool, Portsmouth and Southampton, as a trial for a national scheme. But because much of the ground was already covered by initiatives run by local councils and civic societies, it was decided that the English Heritage scheme would continue to focus solely on London, with advice and guidance offered to others putting up plaques nationwide.

- While the current rule is to only put up one plaque per person, some have two. The record for the most plaques is jointly held by the prime ministers Lord Palmerston and William Gladstone, and the author William Makepeace Thackeray, who each have three.

- A plaque to Karl Marx put up in Maitland Park Road in Chalk Farm in 1935 was twice vandalised by, it’s believed, supporters of the British Union of Fascists. The owner of the property declined to have a third installed. Another plaque to Marx was eventually unveiled in Dean Street in Soho in 1967, where it can still be seen on the façade of Quo Vadis.Words: Oliver Hurley