How did the circus begin?

It’s 1899 and the greatest show on Earth has come to town. In a time before film and television, animal rights awareness and mass travel, a three-mile parade through towns from Torquay to Aberdeen, announcing the arrival of the circus, gives glimpses of a wider world. Children and adults gaze in awe at the dazzling array of acrobats, clowns, horses, wagons and hundreds of mounted elephants prancing past them. And, in a giant big top on the edge of town, on a patch of wasteland transformed into a wonderland, a heavy velvet curtain lifts to reveal trapeze artists soaring through the air, a ringmaster in a red tailcoat and top hat twirling round the ring, lions jumping through hoops and sawdust thrown in the air by the thundering hooves of galloping horses. And, as magically as it appeared, the circus disappears overnight – but not before it has cast its spell. The circus has enthralled, mesmerised and inspired people around the world – from young children to artists and designers – for over 250 years. It was a cabinetmaker’s son named Philip Astley who created the modern day circus as an art form when, in 1768, he began performing daring equestrian stunts in an amphitheatre. While, thankfully, we rarely see wild animals in the ring inBritain today, the circus is currently enjoying a resurgence in popularity. ‘People love it because it’s inclusive,’ says Nell Gifford of Giffords Circus, which she started 18 years ago with the aim of creating a miniature, jewel-like, beautiful circus for village greens. In doing so, she has revived a tradition that was dying out as some of the world’s largest circuses closed. ‘It’s funny, a bit mad, there’s a touch of danger, a bit of glamour and it is for everyone. People can imagine themselves being the performers – it’s a believable fantasy,’ she adds.

Today, Giffords Circus appears as if by magic in towns, cities and villages every summer with its troupe of performers, a menagerie ofhorses, dogs and birds, and velvet-lined wagons to bring old-fashioned Thirties-style entertainment to its audiences. ‘For me, a circus is horses, clowns and tents. It’s sawdust, wagons and people,’ Nell enthuses. ‘I love the tent, the animals… and I love the fact that this is a little community where everyone lives together and helps each other out.’ Horses are the reason circus exists at all. Astley began by opening a riding school on the edge of the River Thames near Lambeth Bridge in London, where he would perform acrobatic tricks on horseback alongside his wife Patty, who would circle the ring on a horse with swarms of bees covering her arms. He was a former Sergeant Major in the British cavalry and, after much trial and error, he discovered that a 42-foot ring was the perfect diameter to make use of centrifugal force, thus enabling him to balance on a horse’s back while travelling at speed. In ancient Rome, a rounded or oval arena used for equestrian and other sports and games was known as a ‘ring’ or ‘circus’ – and so the art form developed by Astley gained its name from the very entertainment space in which it was performed. Astley introduced acts from the fairs and pleasure gardens of London and the boulevards of Paris, bringing acrobats, jugglers, rope-dancers, clowns and strong men together in a show for the first time. He toured Europe, performing for Louis XV at Versailles.

What happened next?

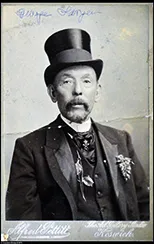

Seeing how much money could be made, other showmen opened circuses and competed to put on the most spectacular and daring shows. By the mid 19th century, hundreds of circuses were operating in Britain with acts becoming more extravagant, exotic and bizarre, from human cannonballs to aquatic performances in flooded circus rings. While theatre and opera were the preserve of the rich and aristocratic, the circus became an art form that could be enjoyed by all. In Victorian times, circuses started touring in wagons and on the newly built railways, which meant its influence was far-reaching. Villages and towns around the world could be visited by a troupe. By the 1870s, huge circuses were travelling across Europe and America with two or three trainloads of equipment. One was the Barnum & Bailey Circus, created by American Phineas Taylor Barnum in Brooklyn, New York in 1871, on whom the recent film The Greatest Showman is based. His parades and shows were some of the biggest and most dazzling ever staged. When Barnum’s circus came to London’s Olympia in 1889 there were 450 performers, 300 horses, 21 elephants, 32 cages and 35 parade and baggage wagons. Englishman ‘Lord’ George Sanger was one of Britain’s leading circus proprietors, known for his signature shiny top hat, who performed for Queen Victoria (a fan of the circus) at Sandringham and Balmoral. His circus, which opened in 1853, toured the country and his parades had all the pomp and spectacle you would expect – his lion-tamer wife travelling in the lead carriage with a lion at her feet.

How did circus influence design?

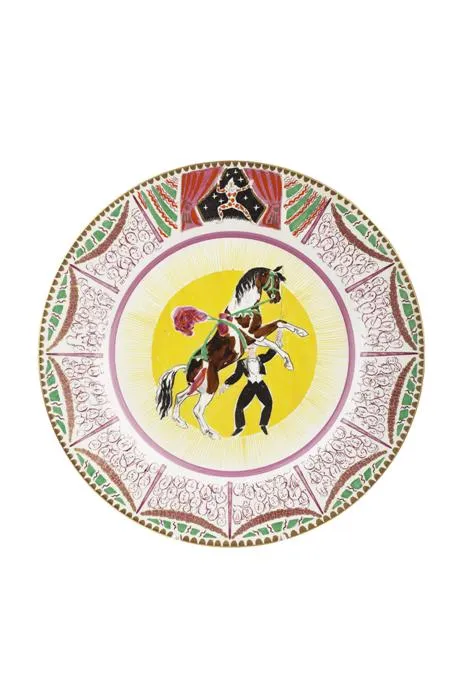

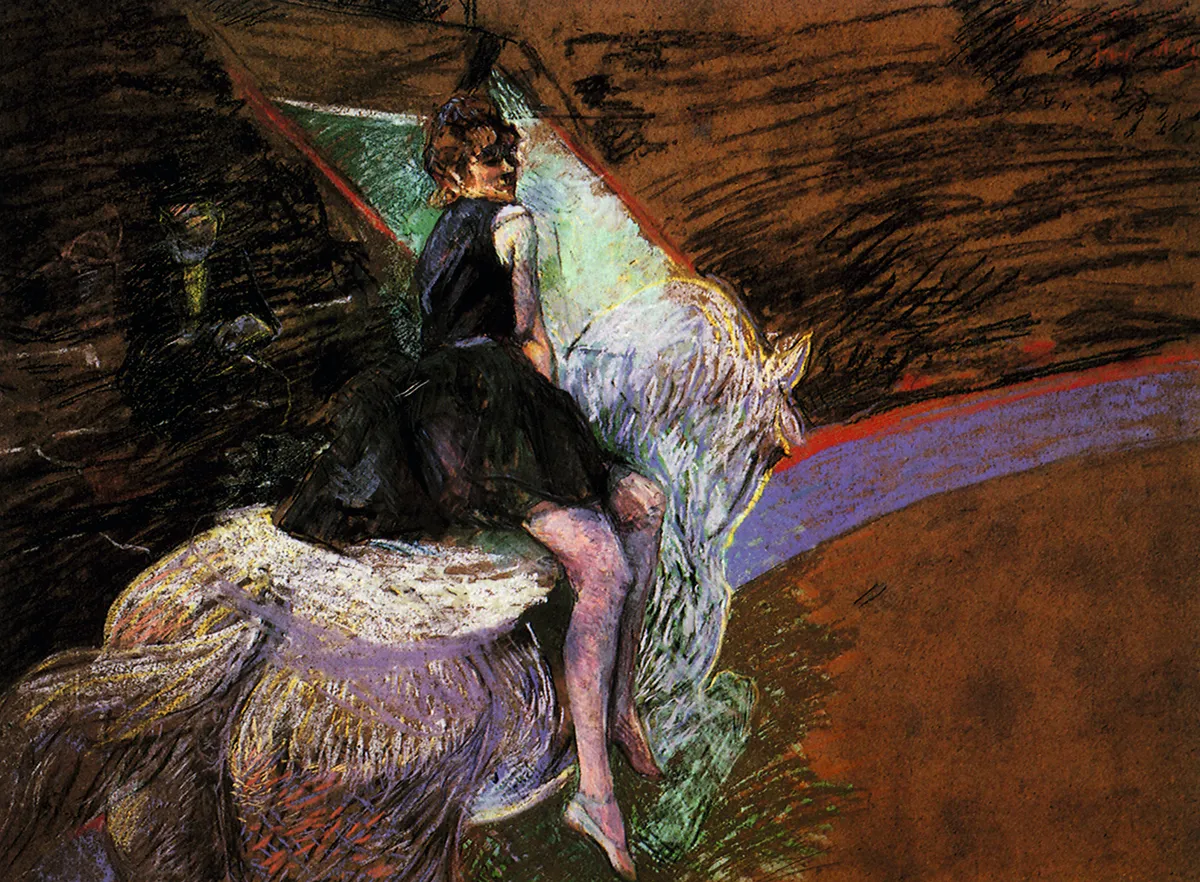

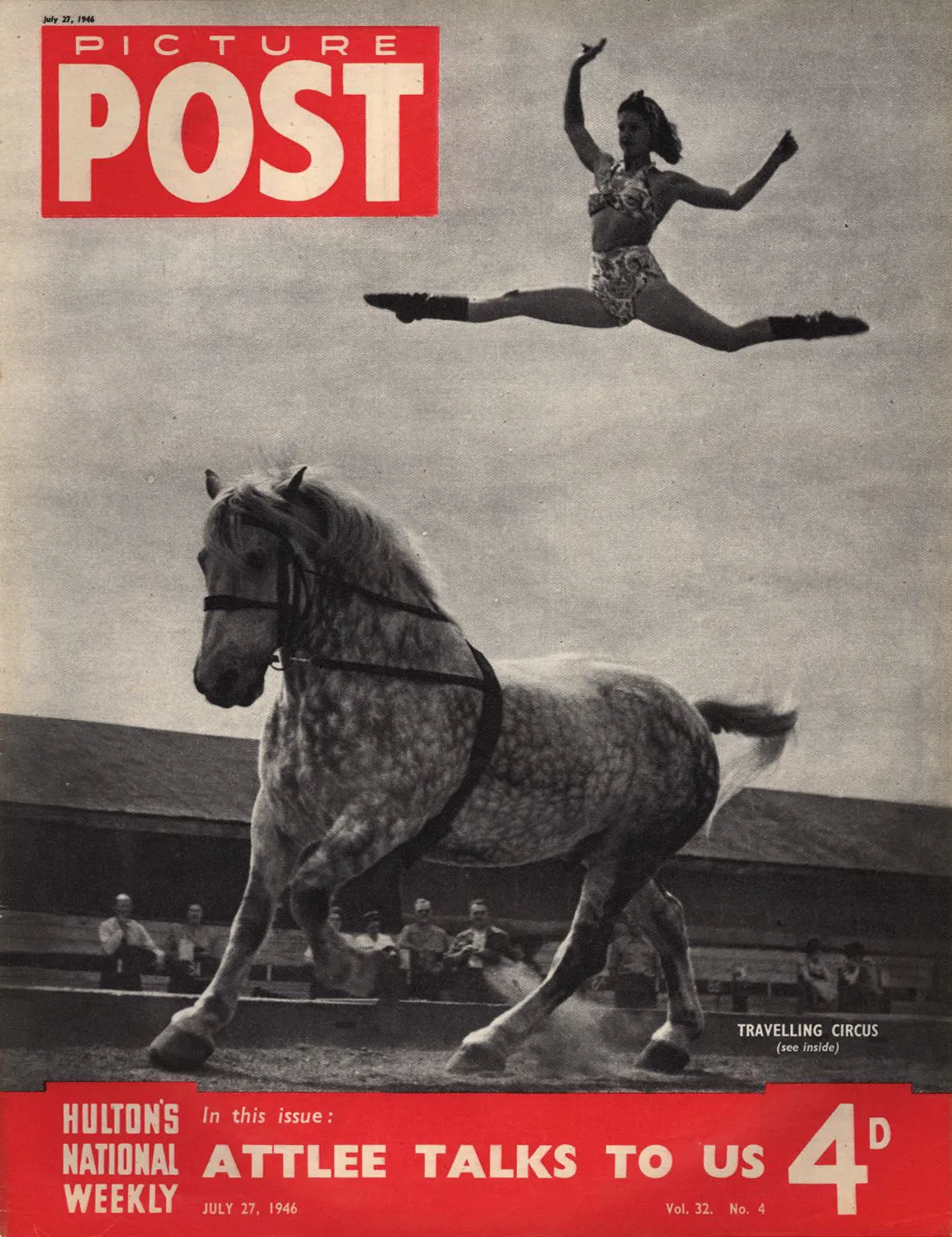

The circus, in all its colour, excitement and drama, has perennially inspired designers and been a muse for artists over the centuries. Georges Seurat was fascinated by the late-night entertainment in Paris and his iconic oil painting Circus Sideshow captures the essence of the Corvi Circus at the annual Gingerbread Fair in 1887. Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Edgar Degas, Walter Sickert, Toulouse-Lautrec and Marc Chagall also used the circus as a theme. In the 1920s, Dame Laura Knight produced beautiful sketches and drawings of the circus. She even travelled with the Bertram Mills outfit from 1927-1929, and she designed a range of circus plates and tableware for Clarice Cliff in 1934. Other pottery can be found depicting the circus, including 19th-century Staffordshire figurines of Victorian lion tamers Isaac Van Amburgh and Ellen Bright as well as equestrian acrobats and clowns. Charles and Ray Eames continuously studied and photographed circuses and, more recently, artist Sir Peter Blake has illustrated his love for the circus, often using circus figures and performing animals in his work. Circus style has appeared on the catwalk too. Alice Temperley embraced it in 2010 and at last year’s London Fashion Week Vivienne Westwood presented a zany circus-themed show. And we’ve seen it in contemporary homeware and interiors. Dutch designer Marcel Wanders produced a circus collection for Italian design brand Alessi in 2016, which saw circus tents, clowns, elephants and strongmen transformed into kitchenware and tableware.

Meanwhile, festoon lights have never been so popular, strung everywhere from children’s bedrooms to eaterie gardens. It comes as no surprise that leftovers from the circus heyday are highly coveted. The colourful promotional posters, which were made in their thousands, are popular among collectors and decorators. But it is the handpainted artefacts as well as the bizarre objects that are most prized and used as conversation-worthy decorative pieces, loved for their folk art qualities. James Gooch of Doe & Hope sells circus antiques and says they have been popular for some time, although the best Victorian examples are extremely rare. ‘Circus antiques blend childlike nostalgia with fun,’ James says. ‘Usually they are very playful but some also have a darker side. Victorian circus items were valued long ago, and they are harder to find now than those from the 1940s to the 1980s.’ Perhaps we all want a piece of the magic? ‘It’s complete escapism, a chance to lift yourself out of normal life,’ ponders Nell.

How does circusmemorabilia sell at auction?

Collectors tend to buy circus-related antiques because of the fond memories evoked. The most common items at auction are the posters, photos and circus toys by makers such as Corgi, Britains and Charbens. Artworks and ceramics by Dame Laura Knight also appear occasionally, selling from £500 up to several thousand. Toys range from £50 for a single item to £300 for a set, while posters start at about £50 and can reach several hundred subject to age, rarity and condition. Handpainted artefactssuch as signs, rides and costumes are rare, but are out there as most 20th-century showmen sold off their effects.

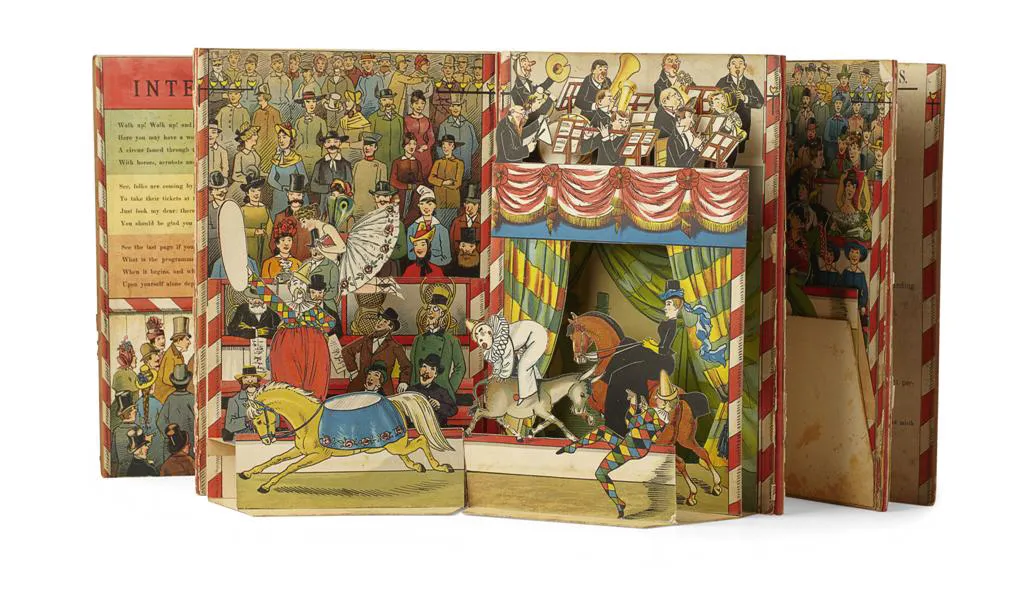

1

A copy of the stunning 1889 pop-up book International Circus by German illustrator Lothar Meggendorfer made £350 at Lyon & Turnbull in September 2015 against an estimate of £200-£400. These beautiful books usually sell for much more but this particular example was missing some sections.

2

A large and rare archive of 150 photographs of the circus of showman ‘Lord’ George Sanger dating from the late 19th and early 20th centuries went under the hammer at Dominic Winter in October 2017, selling for £1,950 when it was expected to fetch £700-£1,000.

3

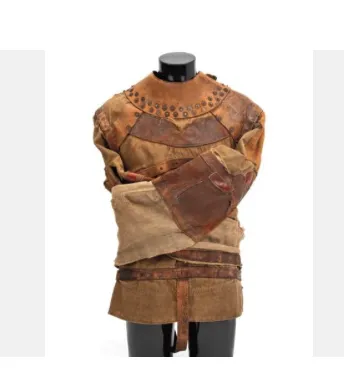

Harry Houdini’s leather and canvas straitjacket c1915 sold at Christie’s in London in November 2011 for £30,000 against an estimate of £15,000-£20,000.

4

A group of late 19th-century tinplate circus toys along with two Crawford’s biscuit tins shaped as a circus wagon and a lion’s cage sold for £500 at Lyon & Turnbull in January 2016 against an estimate of £300-£500.

5

In April 2010, a group of eight Circus dinner plates, designed in 1934 by Dame Laura Knight for Clarice Cliff, sold for £3,500 at Lyon & Turnbull. The estimate was £1,500-£2,000.