Luminous chests of drawers, mirrors and console tables shimmering with mother of pearl inlay set Graham & Green apart from other interiors companies. These majestic pieces of furniture that Antonia Graham and her son Jamie have been selling since the 1990s bring a touch of the exotic to a home – much like their antique counterparts.

They hail from Udaipur, Rajasthan in north-west India, also known as the ‘White City’, a network of temples and palaces where third and fourth-generation master craftsmen work with this exquisite natural material. The hard yet smooth iridescent substance, known as nacre, forms on the inner layer of the shell of molluscs, especially pearl oysters and abalones.

Want to learn more about the history of art but not sure where to start? We've made a list of the best art history and appreciation courses and lectures available online.

India has a long history with mother of pearl, its seas once rich in pearl oysters. When Marco Polo visited the Gulf of Mannar off the southernmost tip of India in 1294, he saw up to 500 ships harvesting pearl oyster beds. And over the centuries, Rajasthan’s neighbouring state, Gujarat, has played a key role in using mother of pearl in decorative woodware.

Want to learn more? Here's everything you need to know about how pearls are formed.

The material is not purely of Indian origin, however. ‘The Ancient Egyptians were using mother of pearl in at least 4200 BC – pieces have been found in pyramids and tombs of the ruling classes,’ says Matthew Thomas, Bonhams specialist in Islamic and Indian Art. ‘From archaeological evidence, we know that mother of pearl was also used by the Mesopotamians as far back as 2500 BC. It was certainly popular in China during the Ming dynasty (1368-1644) – although it had been in use in China much earlier during the Bronze Age of the Shang dynasty (1500-1050 BC).’

From the beginning, mother of pearl was used as it is today – mostly for decorative inlay – and it was both carved and engraved. At first it was thought mother of pearl oyster beds existed in only three regions – the Persian Gulf, the Red Sea and the India-Sri Lanka coast, but European explorers on voyages of discovery found pearl oyster beds throughout tropical waters.

The shells were soon collected and sent around the world as people clambered to own a piece of this lustrous treasure from the sea. In the 16th century, raw mother of pearl from the Philippines would travel in galleons to Mexico and then across land to ships bound for Spain. From the 17th century, China imported raw shell from Indonesia to make gaming counters for rich Europeans, and sold surplus stock overseas.

Meanwhile, the French East India Company was importing raw shell from its colonies and trading with the Far East, stopping at ports in Madagascar and India.

‘It became popular because of its aesthetic appeal,’ says Matthew. ‘Its iridescence is very attractive. It is also durable – its natural function is to protect the inside of the mollusc’s shell. And it is versatile, it can be easily worked and painted.’

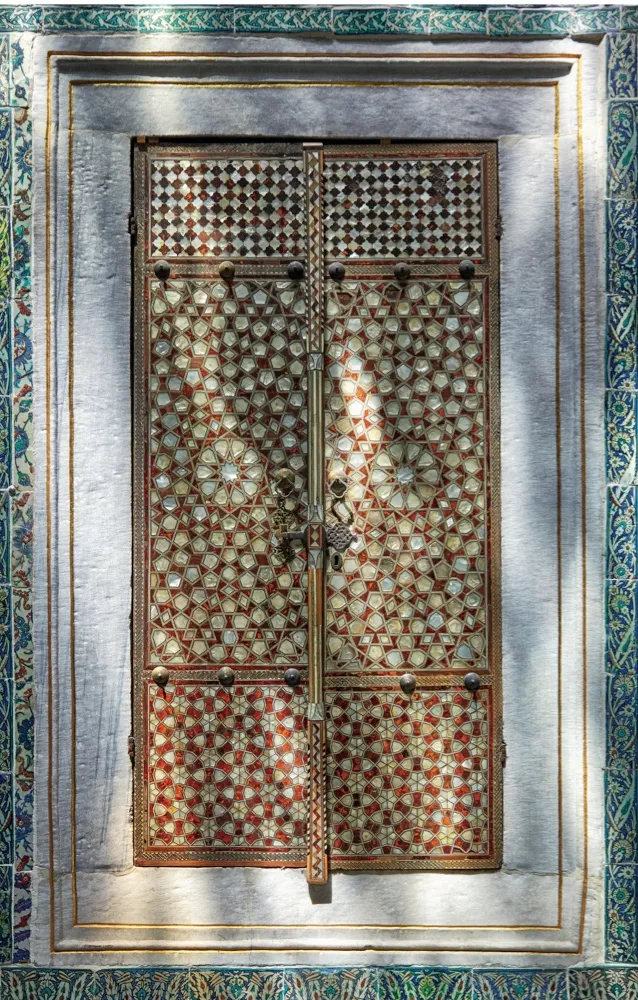

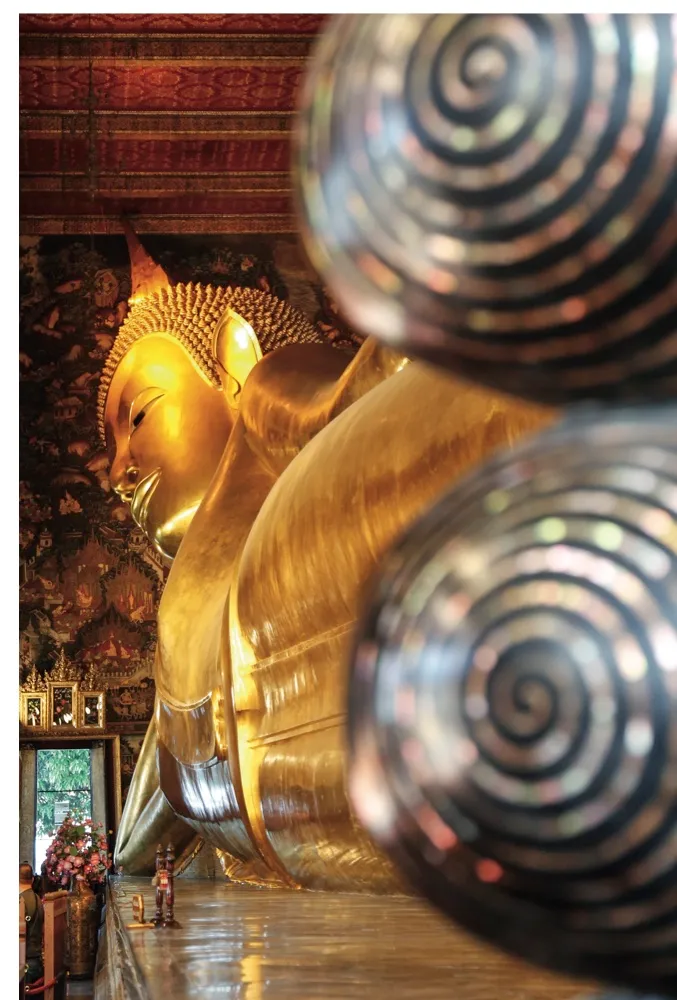

As the popularity of the material grew, major manufacturing centres formed in France, where the town of Méru was considered the capital of pearl making, and England, where itwas used on buttons and cutlery. Palestine also became ahub for mother of pearl craft afterFranciscan monks introduced the art to Bethlehem and craftsmen carvedreligious souvenirs to sell in the Holy Land and across Europe. In places such as Thailand and the Ottoman Empire, it was used in architecture, inlaid in doors, windows, thrones and throughout palaces.

A Worldwide Phenomenon

Mother of pearl reached its height in the 19th century and all manner of items featured the material, including inkwells, snuff boxes, fans and card cases. Production became so intense that thousands of tons of mother of pearl were harvested and transported around the world.

At this time, Broome in Western Australia was supplying much of the world’s raw mother of pearl. Buttons were big business. The fashion for wearing mother of pearl buttons, which started in the 17th century, peaked in the late Victorian period– people in the East End of London took it a step further, adorning entire outfits with them, hence Pearly Kings and Queens. ‘According to one estimate, the button industry was using 300,000 tons of oyster shells a year,’ says Matthew.

After centuries of being plundered,pearl beds around the world no longer thrive as they once did and today mother of pearl is supplied by commercial pearl farms, which makes antique furniture featuring large pieces of unfarmed mother of pearl all the more treasured. ‘It is a luxurious material,’ says Jamie Sinai of Mayfair Gallery, London, which sells mother of pearl antiques including 19th-century inlay furniture from China, Syria and Japan. ‘It has a unique exoticness about it that draws you in.’

Key Designs: Historic creations in mother of pearl

Collecting Mother of Pearl

When it comes to collecting mother of pearl antiques, it’s an interesting field, as such a variety of wares were made in different centuries. It is also a mysterious material, as few pieces have hallmarks or artist’s marks that reveal the place and date of origin. The height of mother of pearl carving in the western world was 1790-1820, when the finest goods were sold in the shops of Palais-Royal in Paris – they were then, and remain to this day, the highest standard of work. Sets of sewing tools, desk accessories, tableware and other fine pieces are highly desirable and are in constant demand by collectors, exhibitors and museums.

Before starting to collect, get to know the material so you can be confident it is natural and authentic. ‘Mother of pearl is always cool to the touch,’ says Patricia Martin, who co-wrote the book Mother-of-Pearl Antiques and Collectibles. ‘Test it by putting it up against your cheek and you will feel a distinct coolness. And examine the piece on all sides. The fact that it may be polished on one side and raw on the other (such as in many buttons) is easy proof that it is real. A fake would be polished overall. Raw, unpolished mother of pearl can have an uneven back and some natural blemishing, while polished shell backs will have the same clean-cut character as the front. Plastics or resins have opaque backs and although they may shine, they lack the luminescence gradient of real mother of pearl. Hold a piece in your hand to get an idea of its weight. The real stuff feels substantial, even heavy, for its size.’

Condition, size, rarity, age, craftsmanship and provenance all affect the value of mother of pearl pieces. Prices can vary quite considerably. A late 19th-century needlework box or card case can cost about £100-£150, a Georgian tea caddy about £3,000, a 19th-century Syrian wedding chest about £7,000, while a large and intricate late 19th-century inlaid Japanese cabinet can be £75,000. Mother of pearl canteens can vary from several hundred to several thousand pounds. And let’s not forget the c1600 wooden tray from Gujarat, which sold for a record £962,500.

‘Smaller boxes, card cases, cutlery and jewellery made on a large scale can be fairly inexpensive – in the hundreds of pounds,’ says Jamie Sinai of Mayfair Gallery. ‘Large, more elaborate pieces, especially furniture, that show great craftsmanship, are rarer and more expensive. They are extremely impressive objects.’

The lustre of mother of pearl can also affect the price, so too do the faint overtones. The light and colours reflected from mother of pearl is part of what makes it so desirable. ‘Good-quality mother of pearl will have subtle lustres that make it shine when light hits,’ says Patricia. ‘Rose and ivory are two of the most desired overtones, although a wide variety of colours are possible, especially for darker examples.’

When it comes to caring for mother of pearl, Jamie’s best advice is to take particular care with pieces inlaid with mother of pearl, as it can be dislodged if knocked or dropped.