The art historian, Sir Kenneth Clark, once admitted that he started to collect antiques because of a ‘sentimental feeling that[he] must rescue them from neglect’. I know exactly what he meant.

I’m writing this at our George III partner’s desk, sitting opposite my wife, Venetia, both of us working from home because of the dreaded lockdown.There are so many books, antiques and objets d’art between us that it’s a lucky day if I can spot the top of Venetia’s auburn locks. We found most of the items, with the exception of an engraved postcard liberated from the desk of Sir Laurence Olivier (a kind present from an understanding friend), languishing in murky corners of country salesrooms. Overlooked and undervalued, they were crying out to be rescued.

For years I resisted the urge to collect (I’ve always had an aversion to stamps), without realising that I was a born collector myself. In the early 90s, I scraped a porter’s job in the shabby secondary salesroom of a famous London auction house. A few years later, I was cataloguing snuff boxes, bronzes and ivory chess sets in the basement of a rival firm in New Bond Street. It was a rare opportunity to handle and examine at close quarters a vast array of antiques and works of art. I began to collect, and I’ve never looked back.

These days I’m a dealer, which not only allows me to nose around other peoples’ houses, but also gives me a marvellous excuse to collect on their behalf. One of my clients keeps a ‘cabinet of curiosities’ – a popular pastime for 17th-century antiquarians with a taste for the bizarre. There is a set of framed tarantulas in his bathroom and on his desk, a telegram from Dr Crippen. One memorable day, from a box beneath his bed, he produced a mummified cat.

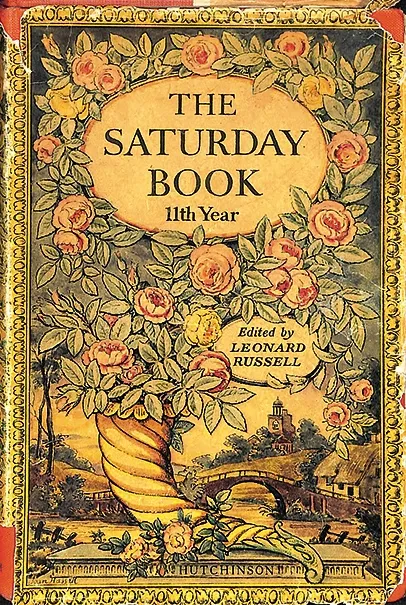

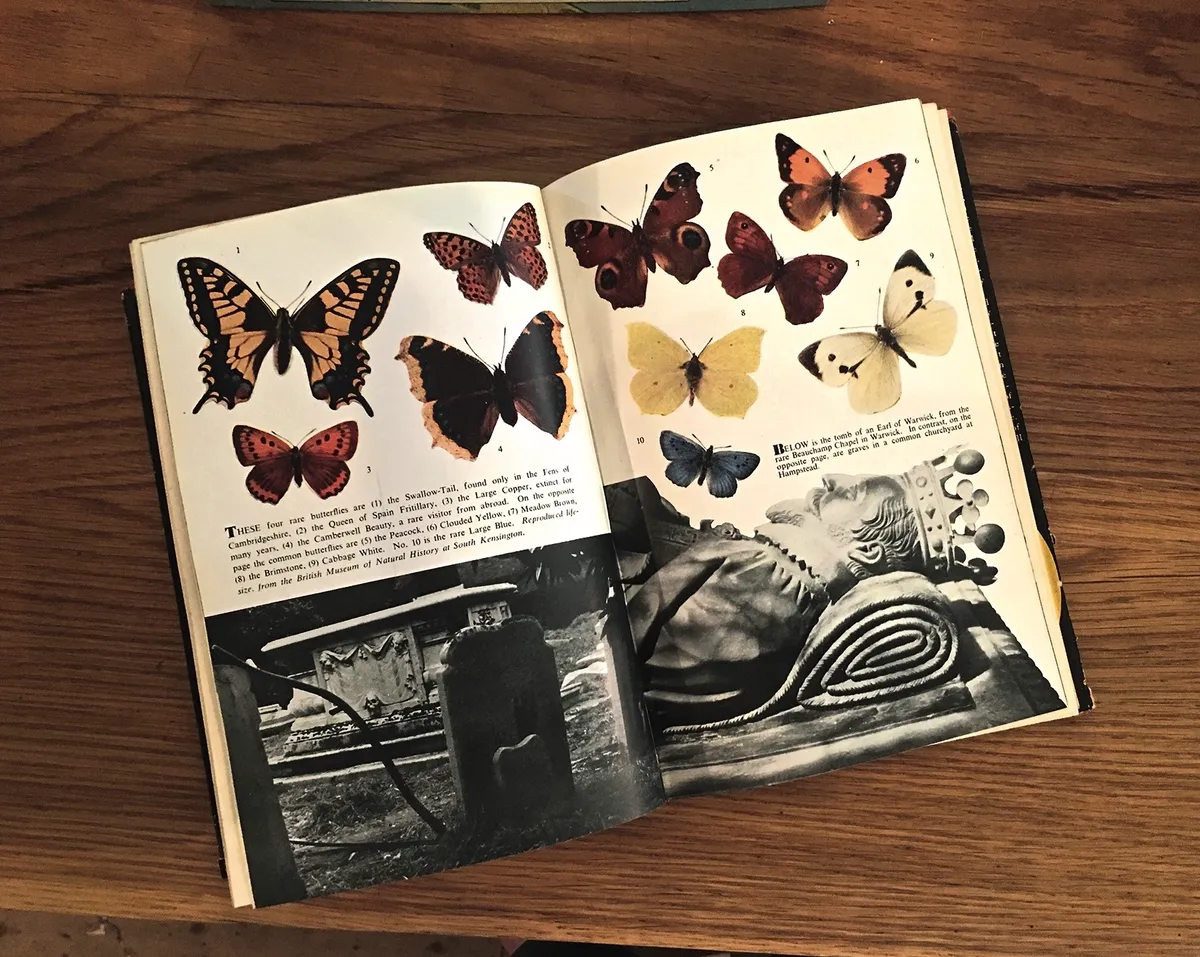

I suppose you’re either a collectoror you’re not – it’s that simple. Collectors tend to be dilettantes or completists, butterfly dabblers in the beautiful or obsessive cataloguers with a scientific bent. Despite my dilettante tendencies, I’m an unashamed completist, and The Saturday Book is my current obsession. This insanely collectable, and much- loved, grown-up’s annual was published every Christmas between 1941 and 1975, and intended as a celebration of British culture during the dark days of the Second World War.

By the mid-1970s, the series had evolved into an eccentric scrapbook of ideas, images and stories from the past. From the fashion photography of Cecil Beaton to glass mezzotints of Nelson, it was a hotchpotch of the useless, beautiful and unusual – which might also be a fair description of the current state of my desk. The contributors list is a roll-call of British 20th-century talent: John Betjeman, Osbert Sitwell, Ronald Searle and Edward Ardizzone.

There are 34 original volumes to collect. Although it is now being rediscovered by a new generation of designers, artists, writers and aesthetes, it’s still possible to find copies online at reasonable cost. Prices start at a few pounds, rising to the low hundreds for the scarcer titles in top condition, with dust jackets. For those of us with a taste for the unexpected, The Saturday Book has it all: it’s as much about discovery, as possession. I hope you will join me over the coming months as we reawaken the spirit of The Saturday Book and explore the fascinating world of collecting in all its forms. Value is not important,it’s about curiosity, enthusiasm and developing an eye.

Luke Honey is an antiques dealer and writer. Find out more at lukehoney.co.uk