What is a parterre?

Originally created to embellish landscaped grounds surrounding royal palaces and chateaux, parterres have remained one of the most enduring of all garden styles. The individual elements of a traditional parterre are simple: symmetrically laid-out beds, low hedging and gravel paths. Yet brought together by leading garden designers of the day, they produced some of the most wonderfully ornate, striking designs in gardening’s rich history.

Often confused with Tudor knot gardens – which can be distinguished by a single, rather than multiple, square frame encasing a pattern or symbol – the more flamboyant parterre didn’t make an appearance until the 17th century.

When did parterres become popular?

Vanishing for a time during the 18th century, when the rigid structure no longer appealed to landscape architects who preferred a more free-form approach, parterres made an astonishing comeback during the 19th century. This time the Victorians preferred them to be filled with the bright colours of exotic species collected abroad and reared in the new technologically advanced glasshouses.

Today, parterres are still very much in evidence and are popular with garden designers, including Chris Beardshaw, who incorporated his interpretation of a parterre in his Morgan Stanley Healthy Cities Garden for the Chelsea Flower Show. So why has such a formal design remained a firm favourite with gardeners, and who do we have to thank for introducing it to British shores?

Who created parterres?

The 17th century was an exciting time for garden design. Royalty was embracing new styles and setting the agenda for fashion. Gardens became status symbols to show how much power and wealth was at your disposal.

French nurseryman and designer Claude Mollet (1650–1742), known as the ‘gardener to three French Kings’, took inspiration from English knot gardens and French embroidery to develop a series of patterned compartimens that featured a simple interlace pattern of herbs filled either with sand or flowers.

Laid out next to the house, with a central path running away from the building, the device was an effective way to create a view that could be enjoyed from indoors as well as accentuating the proportions of the building within its grand surroundings. Interestingly, the pattern was considered to be more important than the planting it encompassed, becoming more intricate depending on the wealth and status of the owner.

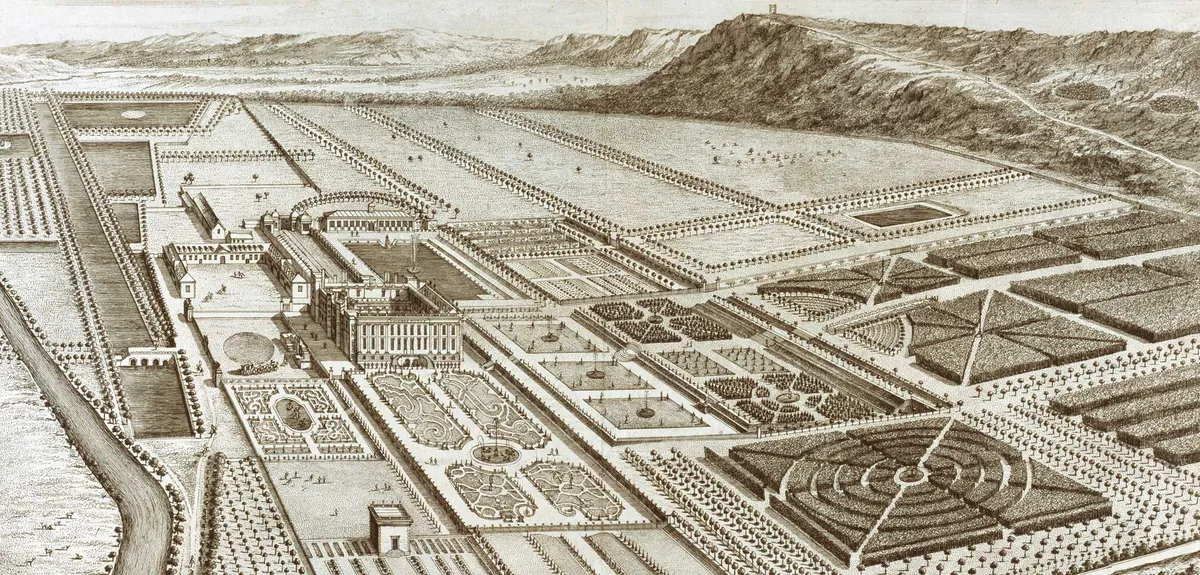

Claude Mollet incorporated his parterres into the prestigious royal gardens of Saint Germain-en-Laye and Versailles by the early 1600s. The French king Louis XIV was an advocate of the design: it was an ideal way to show off his vast wealth and he liked the idea of demonstrating control over the natural world by using such rigid, formal structures and carefully considered plant combinations.

You might also like an elegant parterre garden paired with evergreen structure

Parterres in British gardens

By 1620, Claude’s son, André Mollet, had been summoned to England by Charles I to lay out parterres for his royal gardens. Later that century, Queen Anne’s gardeners George London and Henry Wise took up the baton and created parterres for prestigious gardens owned by English nobility, such as the first Duke of Devonshire at Chatsworth. There, rather daringly, a number of parterres were cut into the slopes above the house and featured an intricate pattern separated by gravel paths.

The sixth Duke continued the tradition by laying out a new rose parterre immediately to the south of the first Duke’s greenhouse in 1811. London and Wise also laid out a large parterre at Badminton House, the family seat of the Duke of Beaufort, but sadly it didn’t survive the changing fashions and was removed in the mid 18th century.

In 1710 the duo also created a series of formal parterres on the upper terraces nearest the house at Canons Ashby. Originally designed for Sir Henry Dryden, they too were removed but have been reinstated in a recent renovation project overseen by The National Trust.

During the mid 1800s, English landscape architect William Andrews Nesfield (1793–1881) led the field of country house garden designers. The prominent horticulturist JC Loudon enthused, ‘His opinion is now sought for by gentlemen of taste in every part of the country.’ He created terraced parterres in elaborate scrolls and arabesque motifs of box hedging set in coloured gravels, with statues and topiary providing vertical accents.

He is credited for creating a terraced double parterre on a ground of white gravel, featuring his characteristic graceful arabesques of box, for the Marquess of Westminster’s Cheshire seat, Eaton Hall.

Today, you can visit some of the largest parterres in the country at the National Trust’s garden at Cliveden in Buckinghamshire, built as a collaboration between the Duke and Duchess of Sutherland and head gardener John Fleming in 1840. Fleming reintroduced the layout of a traditional parterre but with exuberant planting. Covering six acres and with 16 formal beds, box hedging and yew topiary, the recently restored parterre is one of the garden’s most dramatic features.

How the Victorians reinvented parterres

Victorians reinvented the parterre, adding exotic and colourful plants, many imported by the Veitch family.

Parterres came back into fashion in the 19th century, revamped to accommodate the Victorians’ passion for colourful carpet bedding. While designers still used geometrically shaped beds, this time they were filled with colourful exotic bulbs and plants, many of them new to this country and that simply weren’t available to the creators of earlier parterres.

The Veitch family was a horticultural tour-de-force during this period, not only as landscape designers and nurserymen, but as trailblazers orchestrating the huge explosion in the numbers of new and unusual plants introduced to British gardeners.

You might also like a history of Victorian garden cemeteries

By the late 1700s, John Veitch (1752–1839) was a successful landscape designer, working with such prestigious properties as the Killerton Estate (now National Trust). In 1808, he founded a nursery in Budlake, Exeter. He sent plant hunters all over the world to find new plants and seeds, a venture that was profitable and far-sighted. In part, timing was on his side – new technologically advanced greenhouses provided the perfect environment to propagate and raise plants in large numbers, and the end of the Napoleonic Wars meant free passage around the globe.

Suddenly it was possible for plant hunters to travel far and wide, sending their discoveries back home with relative ease. There was an explosion in the variety of new and unusual plants and, for the first time, seeds were arriving in Britain, thanks to the likes of Cornish brothers Thomas and William Lobb and David Bowman, a Scot, who were among the Veitch adventurers who helped shaped the way gardens looked from the Victorian period onwards.

In 1837, John’s son James (Sr) joined the nursery and continued its expansion in Exeter and, from 1853, on Kings Road in London, with his son James (Jr). Soon leading figures, including royalty, heads of state and eminent scientists – including Darwin – regularly paid homage to the nursery, celebrating its new discoveries, plant houses and the introduction of many orchids specimens.

Over the following years, more Veitches joined the family business, including James Jr’s son Harry James Veitch, who was knighted in 1912. The nursery closed in the 1960s and, while the family’s legacy is far reaching, most astonishing of all was its contribution to plant discovery. By the first world war, Veitch plant hunters had clocked up an impressive tally, finding 498 greenhouse plants, 232 orchids, 153 deciduous trees, shrubs and climbing plants, 122 herbaceous plants, 118 ferns, 72evergreens, 49 conifers and 37 ornamental bulbs.

Modern parterres

This versatile feature works well in today’s gardens, large or small, planted with ornamentals or edible.

The essential elements of a parterre make it a perfect design to copy or modify to suit aspect, position and site in your own garden. Although originally created for vast spaces, the parterre is actually a versatile stylistic device that looks just as effective in a country or an urban setting, and whether it is made on a grand or a small scale.

A flat, level surface is best but designers created a parterre on a slope at Chatsworth, so don’t despair if you don’t have a bowling green. Choose a sunny spot and, if possible, position it so that it can be seen from the house, preferably from a first-floor window. Evergreen hedges are best, such as box, hebe or one of the evergreen varieties of euonymus, as they are the perfect foil for spring, summer and autumn flowers, and provide a structure that will look good in winter.

Although flowers were a secondary consideration during the 17th century, one of the main reasons was because there just wasn’t the choice we have today – spring and summer flowers came in white, pink, blue or mauve (red, yellow and oranges weren’t introduced until the following century, in 1730), and there wasn’t a lot of variety and interest available for autumn and winter.

So make the most of today’s bulging seed catalogues and go for colourful annuals and perennials, which work really well within the frame of a parterre. Spring bulbs are an easy way to create uniform patterns and, if time isn’t an issue, they can be lifted and replaced with summer bedding. Herbs and vegetables are an excellent idea if you’re tight on space and want to have a combination of ornamental and edible plants.

You might also like a day in the life of a Chatsworth gardener

The mini parterres at Brilley Court in Herefordshire are a perfect example of using a formal structure to divide up the garden. Symmetry remains key in each of the parterres, while the planting provides a contemporary twist and complements the cottage garden setting.

Old apples trees are underplanted with dark-purple tulips and a froth of forget-me-nots, and encased in neatly clipped square box hedges, while a curved shape is used closer to the house to showcase a colourful collection of spring bulbs, including tulips and camassias. A combination of vegetables and ornamental flowers are grown within the splendid six-bed parterre in the kitchen garden, which also features the trademark path that separates the beds and leads towards the main focal point, in this case an ancient apple tree and glasshouse.