Names such as Chippendale, Sheraton, de Lamerie, Wedgwood, Spode, William Morris and Ambrose Heal trip off the tongue without much thought – but how many businesswomen within the spectrum of the applied arts can you rustle up?

Probably not many. Maybe, you think, this is because women entrepreneurs were almost unheard of in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries.

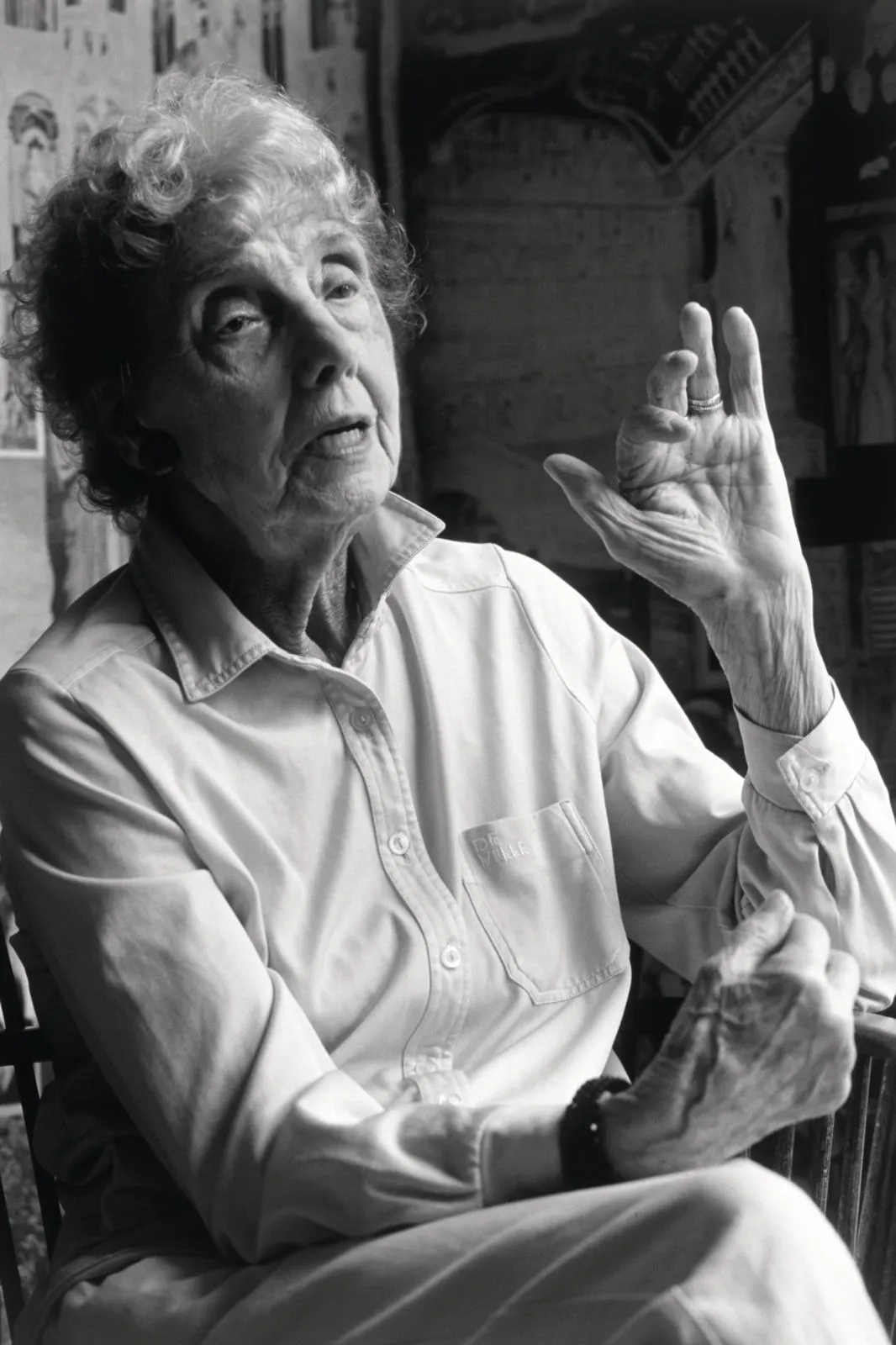

But the truth is rather more complex. ‘In the 18th century it was completely accepted that women might have a business as well as men. The restriction was that they had to do it through their husband’s company or guild,’ says Dr Amy Erickson, Professor of Feminist History at Cambridge University.

How do we know? Amy’s research into 18th-century trade cards reveals many bearing female names. ‘In the City of London, about half of women had a business with their husband and half had a separate business. It’s hard to find a married woman without a business – and I would say this reshapes what we think,’ says Amy.

Hampered by negligible legal rights, and exclusion from many other professions, women were still able to flourish within the decorative arts. Some directed their own businesses after the death of a spouse, or operated in family partnerships. Some developed enterprises that were inventive in the use of trailblazing technology and targeted marketing.

Many names have been lost; a few are more familiar. Either way, acknowledging their achievements adds an enriching dimension to our understanding of women’s role within cultural history.

You might also like the forgotten women of the Arts and Crafts movement

Hester Bateman

Take Hester Bateman, who rose from obscurity to become one of the most successful silversmiths of her day. Having inherited tools and a modest workshop from her husband, she registered her own mark at the age of 52. Hester was probably illiterate, but what she lacked in education she made up for with formidable business talent.

Canny investment in the latest machine technology allowed her to use thin sheet silver – thus keeping prices down and attracting the flourishing middle-class buyers in their droves.

By the mid 1770s, her late husband’s small workshop was transformed into a highly successful enterprise, turning out elegant wares in the fashionable neoclassical taste that remain highly sought after to this day.

Eleanor Coade

Around the same time, and not far away, another intrepid woman plied a very different but equally inventive trade. Eleanor Coade was the daughter of an impecunious wool merchant, who moved to London from the West Country with her parents following her father’s bankruptcy.

After setting up a business selling linen, in 1769, aged 36 and still unmarried, she became a partner in an ailing artificial stone-making business in Lambeth.

Eleanor instigated experiments of her own to create the perfect faux stone. Two years on, she had settled on a recipe – a mix of clay, terracotta, silicates and glass – and parted ways with her male partner, confident she could run the business better on her own.

From a factory that now lies beneath the Royal Festival Hall she produced a weather- and pollution-resistant ceramic substance known as Coade stone.

It was endlessly versatile and much cheaper than carved stone: perfect for making adornments to building façades in smoke-filled cities, or the gracious gardens of country mansions.

Eleanor quickly forged working relationships with the key architects of the day (Robert Adam, James Wyatt, John Nash and John Soane) and she opened a huge showroom near the south end of Westminster Bridge.

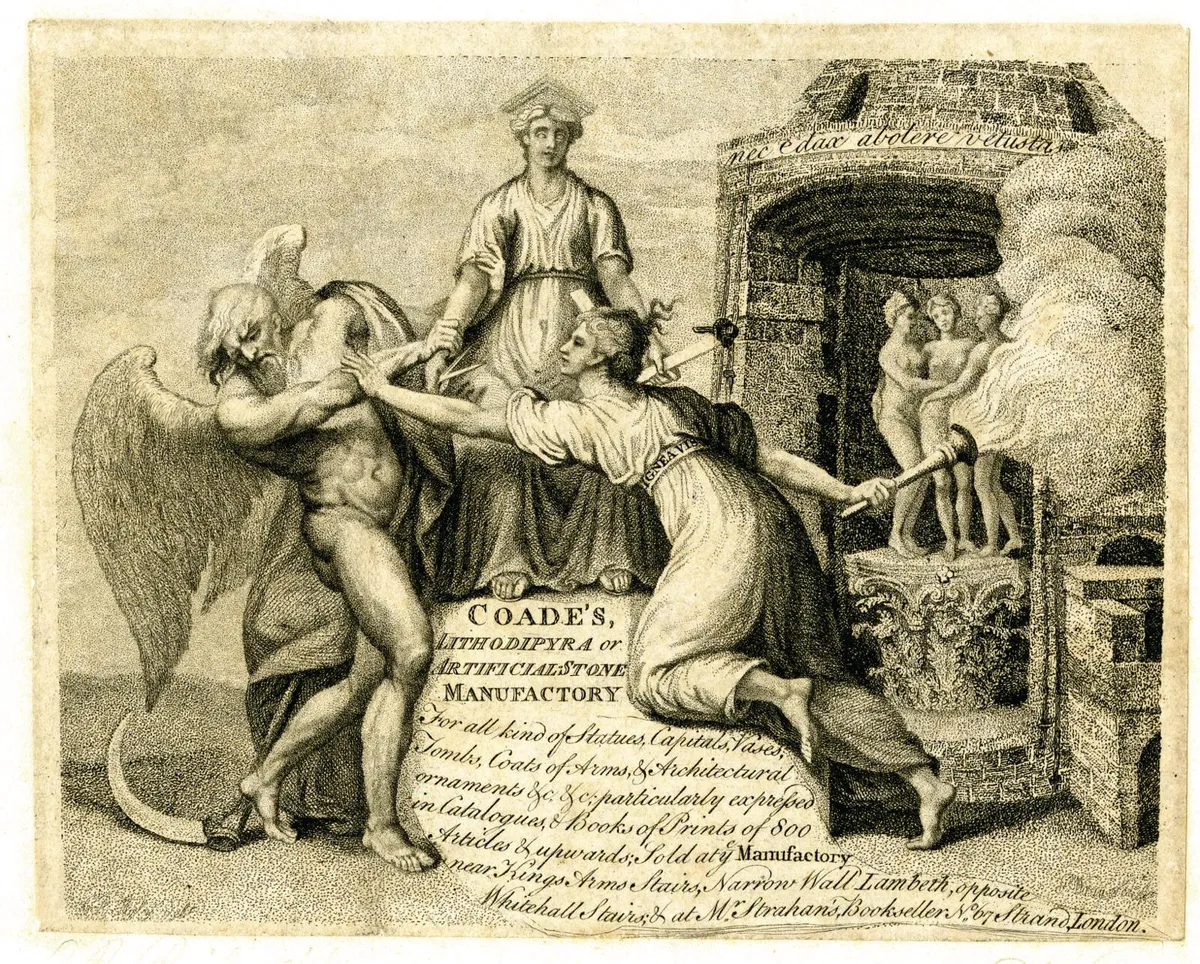

A printed catalogue listed more than 700 products, and an eye-catching trade card featured classical gods empowering her enterprise. Coade stone was sought after around the globe, from Canada, the United States and the Caribbean to South Africa and Europe.

But the progress of women in business wasn’t a linear upward trajectory. Although the 1851 Great Exhibition marked a shift in consumerism, and women were employed in large numbers in menial tasks, those who ran important businesses diminished in number.

‘The nadir comes in the late 19th/early 20th centuries, partly because businesses got larger and separated from home, as people moved to the suburbs. Plus, there’s a heavy emphasis on domesticity,’ explains Amy.

Betty Joel

The unpropitious social climate didn’t prevent exceptions to the trend. Although now an unfamiliar name, Betty Joel was the owner of a much-celebrated Knightsbridge emporium and one of the most influential furniture designers of the 1930s. Betty grew up in the Far East and, having married David Joel, a naval officer, the couple settled in Hayling Island, Hampshire.

With little money, and an eye to establishing a business, they set about furnishing their home with furniture Betty designed. ‘I despaired of trying to adapt old furniture to the needs of my own entirely modern house,’ she later wrote.

Function and elegant modernity were key to her designs: corners were rounded, drawers lined in cedar to deter moths, stools fitted underneath dressing tables and streamlined socket handles completed the sleek look. ‘It was of its time, but it wasn’t avant garde. It was safe,’ says her great-nephew, furniture specialist Clive Stewart Lockhart.

Friends admired Betty’s work and asked her to make furniture for them. Recognising the rising importance of the female market, Betty set out to capitalise on it, taking a stand at the Ideal Home Exhibition to promote her wares. After a tricky start, customer numbers grew, and architects made approaches.

The couple opened a shop in Sloane Street and then, in 1928, moved to larger premises in Knightsbridge. Furniture was displayed in room sets with rugs, lighting and curtains, and the walls hung with paintings, often by female artists such as Laura Knight, Marie Laurencin and Anna Zinkeisen. By then the prestigious clientele included Winston Churchill, Lady Edwina Mountbatten, Gertrude Stein and The Savoy Hotel.

Betty appeared to be at the pinnacle of success, winning awards for her designs and, with around 80 employees on her payroll, she was ‘among the few women in the history of furniture designing who have touched anything like eminence in this most specialised craft,’ wrote the Daily Mail.

But all wasn’t as it seemed, says Clive Stewart Lockhart. ‘There were marital strains and, despite a high profile, she wasn’t making much money.’ In 1938 the couple separated; Betty walked away from the business and never designed again, and her once illustrious name sank into oblivion.

Susie Cooper

Within the pottery industry of the early 20th century, there are female names whose fame, unlike Betty’s, has endured: Clarice Cliff, Charlotte Rhead, and Daisy Makeig-Jones among them.

But leading the field, in terms of running her own successful enterprise, Susie Cooper reigns supreme. ‘All the others were paid hands on a salary. Whereas being the designer was only part of Susie Cooper’s story – she was managing director, and finance director as well,’ says ceramics expert Paul Atterbury.

Like Betty Joel, Susie’s business model was underpinned by her savvy realisation that demand for ceramics was driven by women, and she could offer what they needed. Her rise to become a key player in the pottery world was extraordinary. Born in 1902, she studied at Burslem School of Art before working as a paintress, primarily at Gray’s Pottery, where she became the factory’s designer.

Then, aged 27, ignoring Gray’s warnings of certain failure, she leased production space at the Crown Works to set up Susie Cooper Pottery, alone.

Taking ‘elegance combined with utility’ as her mantra, she pioneered new production methods and perfected lithographic printing to create multicoloured decoration of high quality. Soon she was supplying famous stores such as Harrods, Peter Jones and Selfridges.

In the 1950s her attention turned to bone china and she established a new company, where elegant ground-breaking shapes, such as the design classic coffee can, also found a ready market. Even when the company eventually joined Wedgwood she remained involved, leaving only when the Crown Works closed.

To Paul Atterbury, her career was a crucial one for generations of women following on in the industry. ‘In a way she paved the way and passed the baton on to Susan Williams-Ellis, the founder of Portmeirion, and Emma Bridgewater, who flourishes to this day. Women understand the market; they know who they are selling to. That’s always been the key to understanding their achievement, and it needs to be more widely acknowledged.’