There are many theories about why and when Valentine’s cards were originally sent, but we do know that they were popular in their simplest, handmade form from the beginning of the 1800s – the first record of a posted Valentine’s card was in 1806.

Far too bold an item to be sent from a woman to a man (though, as my collection attests, women frequently sent them to female friends), it was men who first seized upon them.

As early as 1797, verses and sentiments could be copied and penned with love from The Young Man’s Valentine Writer – a sort of crib sheet for love-stricken romantics. Most of these lines would be written into card cut by knife by the young man himself.

This would then be presented on gilt-edged or decorative sheets of fine paper, and often discreetly folded. Not until the 1820s did a similar tome of ‘Approved Valentines for the use of the Female Sex’ appear.

When were Valentine's Day cards popular?

By the 1830s, around 60,000 Valentine’s cards were being sent each year. And in 1835, Francis Freeling, the Secretary of the Post Office, wrote to the Postmaster General asking for extra expenses for the letter carriers to help them ‘get through the extraordinary exertions’ of the period.

In 1840, the development of the pre-paid penny postage system opened up the market even further (prior to that, the card’s recipient had been made to pay for the service).

With improving production methods – and, no doubt, an inkling of the profits to be made from tender hearts set a-flutter – manufacturers really went to town. At first, the cards were finished by hand, with heavy fringes, spun glass, imitation gems, mother of pearl and even shells being stuck on.

Based on the real thing and every bit as intricate, paper lace, said to have been created by one Joseph Addenbrooke in 1834 while he was working for London papermaker Dobbs & Co, was a big hit of the time.

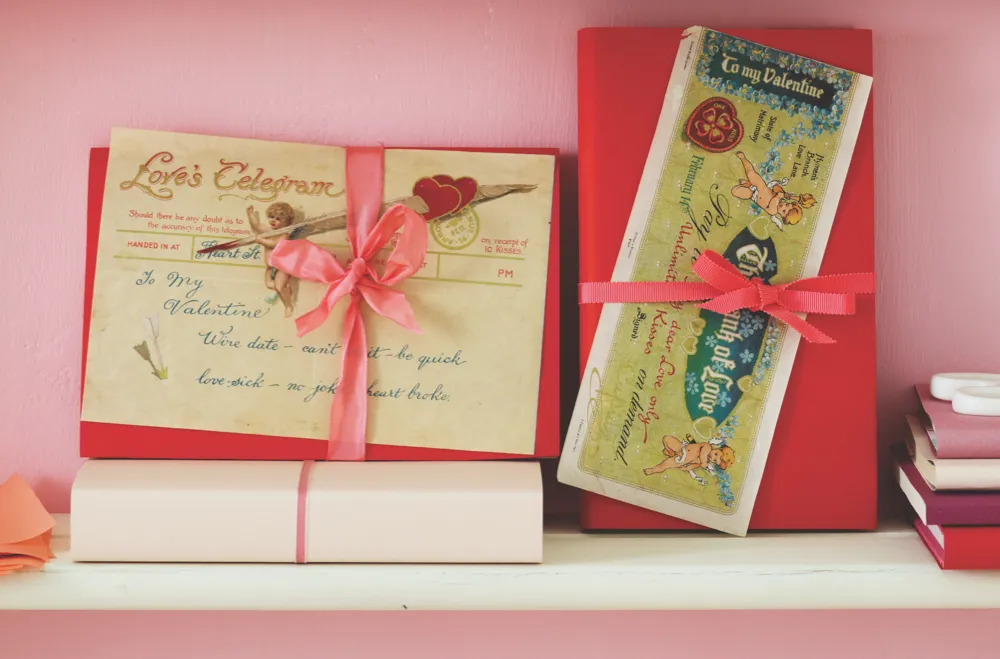

One of the earliest cards in my collection (c1840s-50s) is an exquisite confection of a handmade, gilded cornucopia bursting with handcut flowers bearing aloft a hand-painted cherub, all of which sits within a scallop-edged, paper-lace border. ‘Though far from you, my heart is true,’ is the touching, handwritten message.

As the process of chromolithography became cheaper around the 1860s, many beautiful paper scraps were introduced and the fun really began.

Motifs of printed flowers, birds, borders, cherubs and inscribed books were added to Valentine’s cards, with layers often being supported on little fold-out card ‘springs’ for a 3D effect.

Embossing, gilding and applied feathers, ribbons or even tiny embroidered panels (a speciality of Thomas Stevens of Coventry) added impact (if not subtlety), while other cards featured tantalising tabs that revealed ‘mechanical parts’ such as a moving figure or a waving hand.

As time went on, so die-cut shaped cards made their debut – first as hearts and then as hot-air balloons, pop-up messenger boys, horseshoes and almost anything else you can think of.

One of the most elaborate in my collection (c1920) is a three-layered, pop-up windmill implausibly perched on a rose-wreathed balcony, while another – intriguingly inscribed, ‘To Mrs Anspaugh, from Gordon G’ – opens into an exuberant carousel of love, all made from coloured honeycomb paper.

Who were the key makers of Valentine's Day cards?

Dozens of makers sprang up over the years, but among the best British firms were Dobbs & Co of Fleet Street, A Park of St Leonard Street, Marcus Ward and Joseph Mansell, which specialised in filigree papers and other skilled work.

Eugene Rimmel (of London and Paris) was known for his scented cards, while Raphael Tuck’s cards, printed in Germany, were synonymous with quality, as were those of another German-based publisher, Ernest Nister, which set up a London office in 1888.

Look out for Nister’s charming Valentine’s telegrams, produced in conjunction with EP Dutton of New York but printed in Bavaria. Other American names of note include Esther Howland and George Whitney – to whom Howland sold her business in 1881.

What are Vinegar Valentines?

Introduced by the New York City publisher John McLaughlin in 1858, these comic, mischievous or downright cruel Vinegar Valentines cards were in sharp contrast to the delicate, beautiful examples of earlier years, and were a craze from the late 1800s until the early 20th century.

Often crudely printed on pulp paper and later on postcards, they poked fun at various annoying ‘types’, from image-obsessed dandies to overweight ‘car-seat hogs’, and are a collecting field of their own today.

Luke Honey's cabinet of curiosities: Vinegar Valentines

Our columnist, antiques dealer Luke Honey, considers the compulsion to collect and shares his latest obsession: Vinegar Valentines...

How much do antique Valentine's Day cards cost at auction?

The Royal Mail estimates the most expensive card in its collection to be a handmade, fold-out puzzle card dating back to 1790, which it reckons could reach up to £4,000 at auction – although it has no intention of selling.

Happily, though, most Valentine’s cards are much, much cheaper, with starting prices as low as £10. Prices have remained steady over the years, though they’re rising at the top end of the market as the more sought-after cards are bought up for private collections, leaving fewer cards available.

I often come across Valentines stuck into Victorian scrap albums, too – expect to pay £200 or more, depending on their age, condition and size.

The best Valentine's Day cards to buy this year

Looking for a beautiful Valentine's Day card to woo your loved one? Here's our edit of the most fetching options on the market this year...

Love Valentine's Day card

Buy love Valentine's Day card from Oliver Bonas (£3.95)

'Extra Extra' Valentine news card

Buy Valentine news card from Paperchase (£3.50)

Emma Georgina cotton-covered love card

Buy Emma Georgina cotton-covered love card from Liberty (£4.95)

Folk heart Valentine's Day card

Buy Folk heart Valentine's Day card from Papier (£3.50)

Vintage Valentine's greeting card