Every year, Royal Mail handles an estimated 22 million Valentine’s Day cards; with 2.6 million people sending cards to themselves. February 14th still puts me in the mood for love, despite a singular lack of cards received in my teenage years.

At school, other boys received multiple cards in pink envelopes. I was lucky if I got an ‘anonymous’ card, supposedly sent by a secret admirer, but, in truth, from my sympathetic parents.

What is the history of St Valentine's festival?

The festival of St Valentine has mysterious origins, spanning 600 years. Strangely, the two historical Saint Valentines (a bishop from Terni in Italy, and a 3rd-century priest from Rome, martyred on 14th February) have no connection with romance.

But, by the late Middle Ages, the idea that birds mated on the first day of spring had taken root. Certainly, by the 18th century, lovers were exchanging chocolates, handmade tokens and cards adorned with flowers, turtle doves, love-knots and pretty romantic symbols.

When did people start sending Valentine's Day cards?

Commercially produced valentine cards did not appear until the early 19th century and were sent, or given, by the wealthier classes. At that time postage was expensive (more than a typical working person’s daily wage), and paid by the receiver, not the sender.

But, in 1840, the invention of the pre-paid penny postage stamp meant that, for the first time, love-sick hopefuls might send a cost-effective anonymous card to their crush. By 1841, 400,000 valentines were posted in England alone. The press called it ‘Valentine Mania’.

What are Vinegar Valentines?

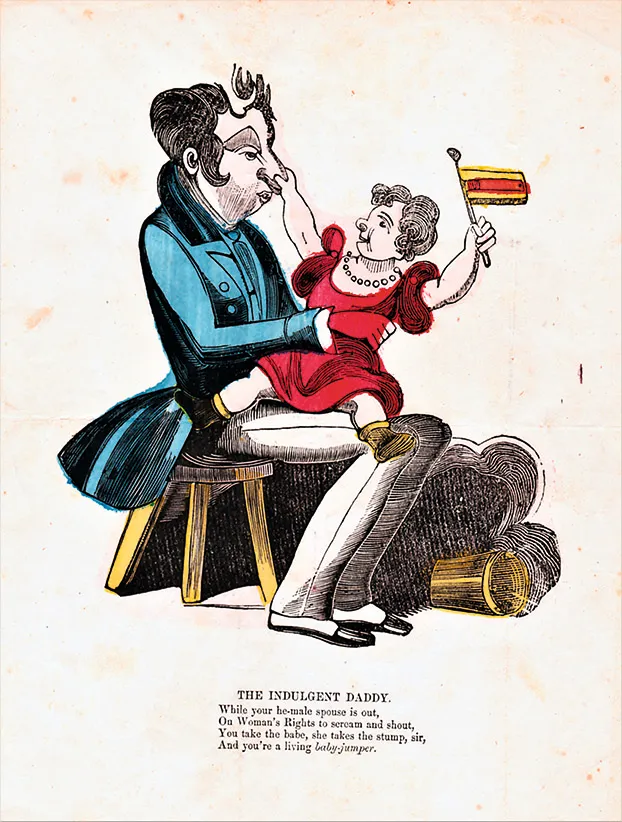

This, alas, meant you could also send insulting cards – humorous and offensive parodies – to those you disliked. During the mid 19th century, thousands of so-called ‘Vinegar’ or ‘Reverse Valentines’ were printed – and received – by unfortunate men, and women, too.

‘Vinegar Valentines’ were simple affairs: mass-produced on cheap, foldable paper, with coarse illustrations, and often accompanied by a crude ditty spelling out the faults and imperfections of the luckless recipient.

They varied from the lightly mocking to the truly nasty. A middle-aged man might be teased, say, for his baldness, for his vanity or pomposity, or for being too submissive; an older woman for being a gossip; a young girl for a shameless flirt.

‘Vinegar Valentines’ are quite hard to find now, despite being printed in great numbers. It’s not surprising when you think about it – most of the victims must have thrown them away on the day they were opened, and who can blame them?

A few years ago, I discovered an excellent example in a Lewes junk shop, framed, and dating from the 1860s. It featured a young man with pince-nez and brown bowler hat, with a slippery reptile at his feet. The caption read:‘To a Snake in the Grass’.

By the end of the 19th century, Valentine’s Day went into decline. In February 1894, The Graphic reported that ‘St Valentine’s Day... attracts very little attention in England’, although, in America, the festival carried on as before.

Then, during the 1950s, Valentine’s Day enjoyed a renaissance in Britain, re-exported back to these shores from the United States, where the greetings card industry enjoyed a significant commercial boom in the years following the Second World War.

How much do antique Vinegar Valentines cost

A careful selection of historical valentines would make an unusual collection. Handwritten valentines from the Georgian and Regency periods come up for sale from time to time.

A sweet valentine from the late 18th century, adorned with hand-painted old roses and love hearts, fetched £360 at Hansons last October.

Later ‘Vinegar Valentines’ are rare (especially cards dating from the mid 19th century) – expect to pay in the region of £150 from a specialist dealer. And, if this sort of thing appeals, ephemera fairs are worth investigating.

Luke Honey is an antiques dealer and writer. Find out more at lukehoney.co.uk