When we say Staffordshire in relation to porcelain, we really mean the area that has become known as ‘The Potteries’. Today, this is the city of Stoke-on-Trent, but in the 18th century the area originally consisted of six towns: Burslem, Hanley, Tunstall, Longton, Fenton and Stoke.

Nestled in the hills north of Birmingham, south of Manchester and east of Liverpool, up to about the year 1700 this was a rural area dotted with tiny villages and a total population of no more than a few thousand people. But what made the area special is that these unassuming villages were sitting on unusually complex layers of clay and coal deposits; the two most important ingredients for making pottery.

We can safely assume that there was something of a cottage pottery industry as early as the 14th century, when church records first mentioned names such as ‘Potter’ and ‘le Thrower’. The next historical clue is a 16th-century court document showing that a certain Richard Denyell was fined for digging holes in the main road in Burslem – and there are many more such fines recorded since then, so locals wrecking the king’s roads in the service of ceramics seems to have been a common problem!

By the 17th century, potters in Staffordshire had developed several kinds of pottery, including simple red-coloured unglazed wares, such as the Elers brothers’ teapot pictured below and bold lead-glazed and salt-glazed pieces featuring interesting colours and tortoiseshell or striped decorations. Production was unmechanised and centred around families making pots in small home-built backyard studios.

But with Britain’s fast-growing population, so the hunger for pots increased all over the country, and it was only a matter of time before some smart young sons of this community seized the opportunity to modernise their industry. And Josiah Wedgwood, born in 1730, was one such moderniser.

Wedgwood was a brilliant innovator and a fascinating man and we’ll return to him more fully in another column. For now, it’s enough to know that, among other things, he was behind four key advances: inventing the pyrometer, which allowed potters to control kiln temperatures; mechanising fine white creamware production; introducing the engine-turning lathe; and using a steam engine to grind flint. But perhaps most importantly, Wedgwood headed up the huge effort to establish the Trent & Mersey Canal, which was completed in 1777 and allowed The Potteries to participate more fully in the Industrial Revolution.

In the 18th century, many beautiful pieces of china met a premature end on a bumpy ride in a horse-drawn carriage over muddy roads full of potholes. In the days before bubble wrap, porcelain was packed in wooden crates with straw. At the same time, those horse-drawn carriages could not possibly carry the enormous amounts of clay and fuel needed for a well-functioning, industrial pottery.

The opening of the new Trent & Mersey Canal solved both of these problems. Huge quantities of coal could be brought in from the collieries in the east, while clay arrived from the south west, via Liverpool. Meanwhile, the resulting wares were safely shipped, bump-free, back to Liverpool, which was fast becoming one of the world’s busiest harbours, bringing enormous rewards to this former rural backwater.

Wedgwood wasn’t the only innovator – John Sadler invented transfer printing, which Josiah Spode took a step further by applying the printing press to the process. A bit later, once porcelain was established in Staffordshire, it was Spode who would standardise the bone china recipeto the formula that is still used all over the world.

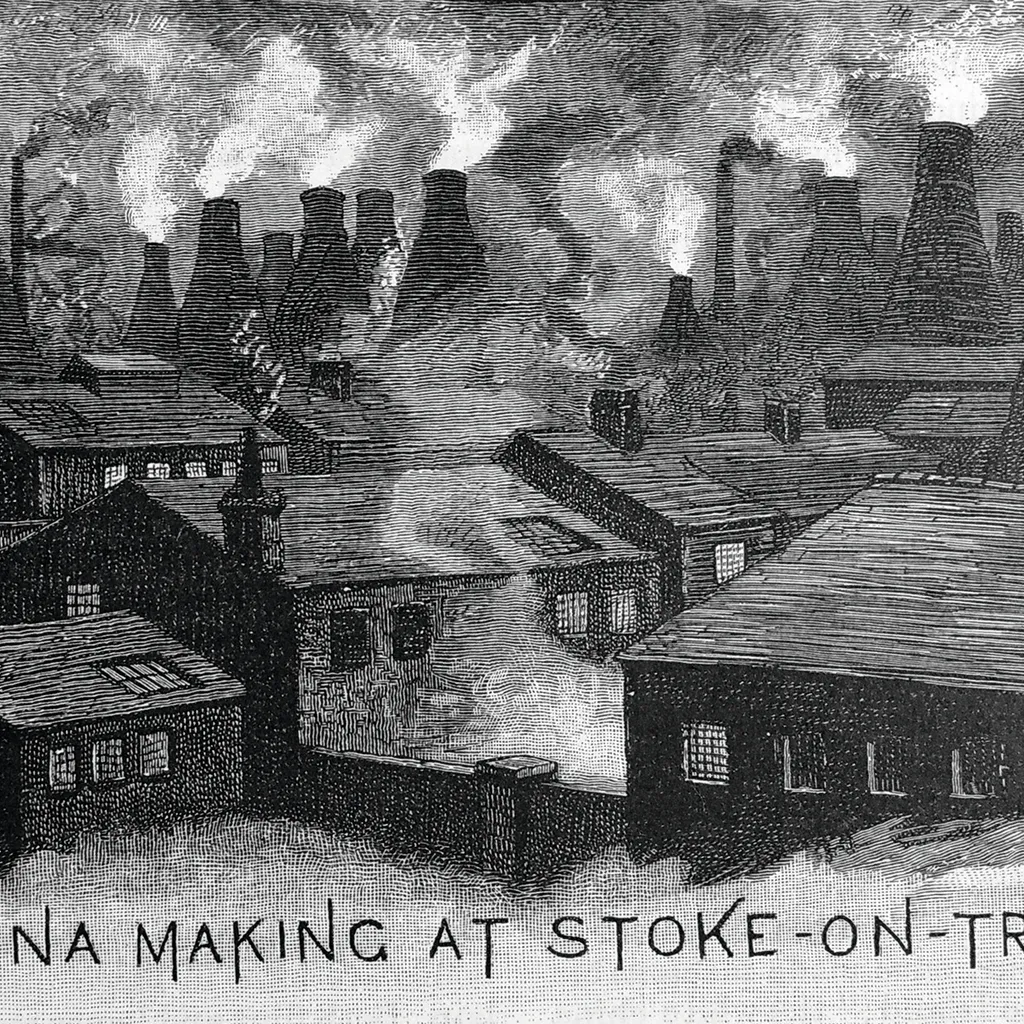

By 1785, there were 200 potteries in Staffordshire, employing 20,000 people, which points to a staggering rate of growth in the 18th century alone. In the hilly landscape of The Potteries, about 1,000 bottle kilns were billowing out their smoke into the previously pristine sky.

And so the familiar image of the Staffordshire Potteries was born: a sprawling patchwork of towns, bottle kilns everywhere you looked and a large population busily employed. Soon, The Potteries would supply the entire world with beautiful porcelain.