There’s no doubt Crittall is having a moment – and has been for a while. If your home doesn’t feature the sleek, usually black, steel windows, famed for their ‘boxed’ frames, then, chances are, they appear in the image in your head of your dream home. When it comes to interiors, they’re the epitome of cool.

Over the last decade they’ve gained ubiquity in the style ranks, joining the likes of cast-iron baths, waterfall showers, range cookers and kitchen islands at the top of people’s wishlists. The look has filtered down to accessories, too – so if your budget doesn’t allow, you can opt for a Crittall-style shower screen or mirror.

As Kate Watson-Smyth says, ‘they fit with any style of house, adding character to everything from classic Georgian to a modern boxy extension. They’re trend proof.’ This is remarkable, considering the brand was born in the late 19th century. Not only did the company pioneer the large-scale production of engineered steel windows but it helped facilitate entire architectural movements…

How Crittall began

In 1849, Francis Berrington Crittall took over an ironmonger’s in Braintree, Essex, and set up home above the shop with his new bride, Fanny Godfrey. Ten children followed, and after Francis’s death in 1879, eldest son Richard inherited the business, handing over to Francis Jr two years later.

He began by diversifying the manufacturing side, directing his small team of craftsmen to make everything from bicycles to bridges, street lighting to drainage. Bolstered by success – the firm now boasted an order book stretching all the way to Liverpool – in 1884 Francis began experimenting with the product that would light up the world.

Slender Frames

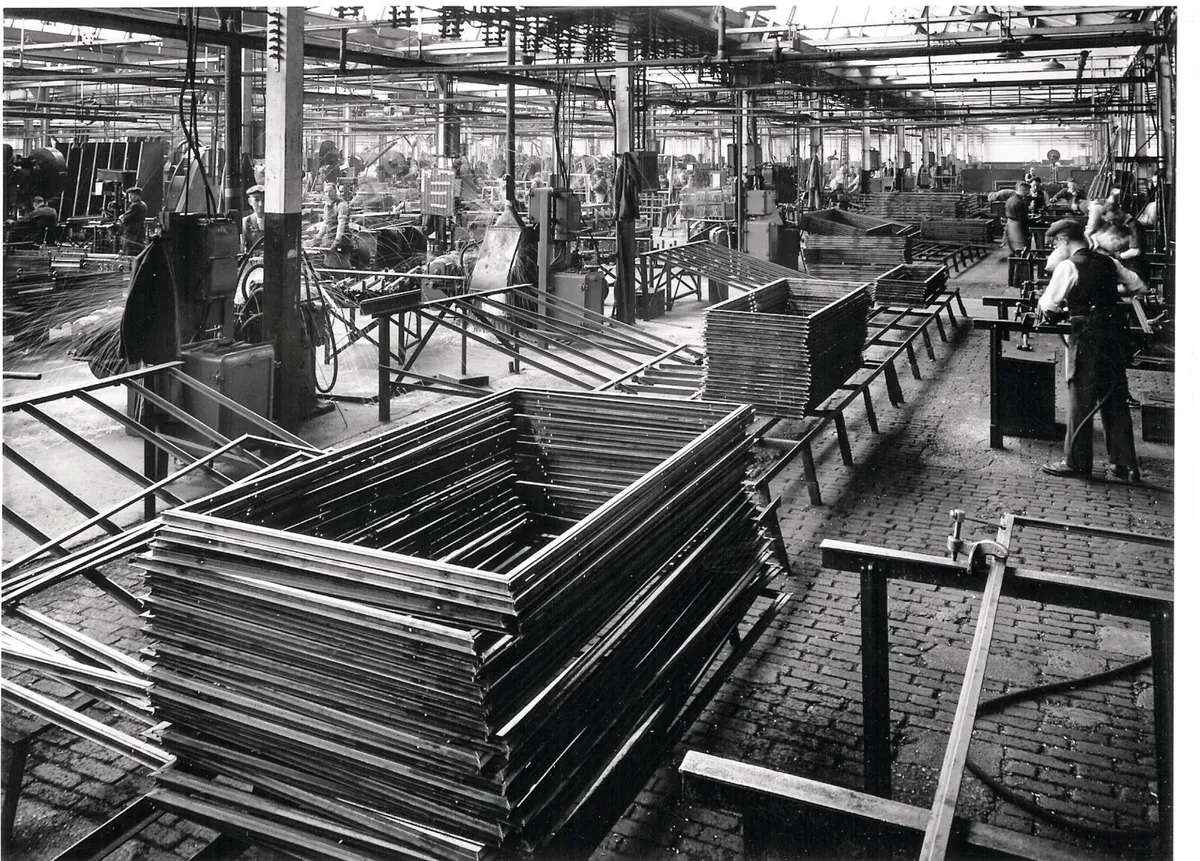

Metal windows had been around since the mid 16th century, but were both heavy to operate and, being individually crafted, time-consuming to manufacture. Crittall’s lighter, slender frames proved so popular that, within a decade, a new factory had been built and the 11-strong workforce inherited by Francis had grown to 60; come the end of the Great War, the number would be 500.

There were two key reasons for the growth. In 1907, Crittall bought the Fenestra joint patent from the Düsseldorf company of the same name, enabling both increased production and slimmer glazing bars. That same year, the firm established its first overseas factory in Detroit, where their wares helped illuminate the factories of the nascent car industry.

Operations in numerous countries would follow, as modern architects such as Walter Gropius and Frank Lloyd Wright helped popularise the use of large steel-framed windows. Notable adoptees of Crittall’s output would include Yale and Princeton Universities, The Big Ben Tower in London, some parts of The Houses of Parliament and, notably, RMS Titanic.

Homes Fit for Heroes

Francis’s two elder sons – Valentine George and Walter Francis – joined the firm shortly before the outbreak of war. Together, they ensured Crittall was ideally placed when prime minister Lloyd George backed the recommendations of the 1918 Tudor Walters report, detailing how best to meet the demand for ‘homes fit for heroes’, and set in place a low-cost housebuilding programme.

Francis Crittall not only manufactured the first standard ‘cottage windows’ for the scheme at his new Witham factory, opened in 1919, but built an estate, Clockhouse Way in Braintree, comprising 65 flat-roofed concrete houses designed by Walter and described by Finn Jensen as ‘Britain’s first cautious steps in Modernism’. ‘Dark frames work like a picture frame,’ says Kate Watson-Smyth, on the benefits the estate’s residents would have enjoyed. ‘It draws your eye beyond the room to the space beyond.’

Healthy Living

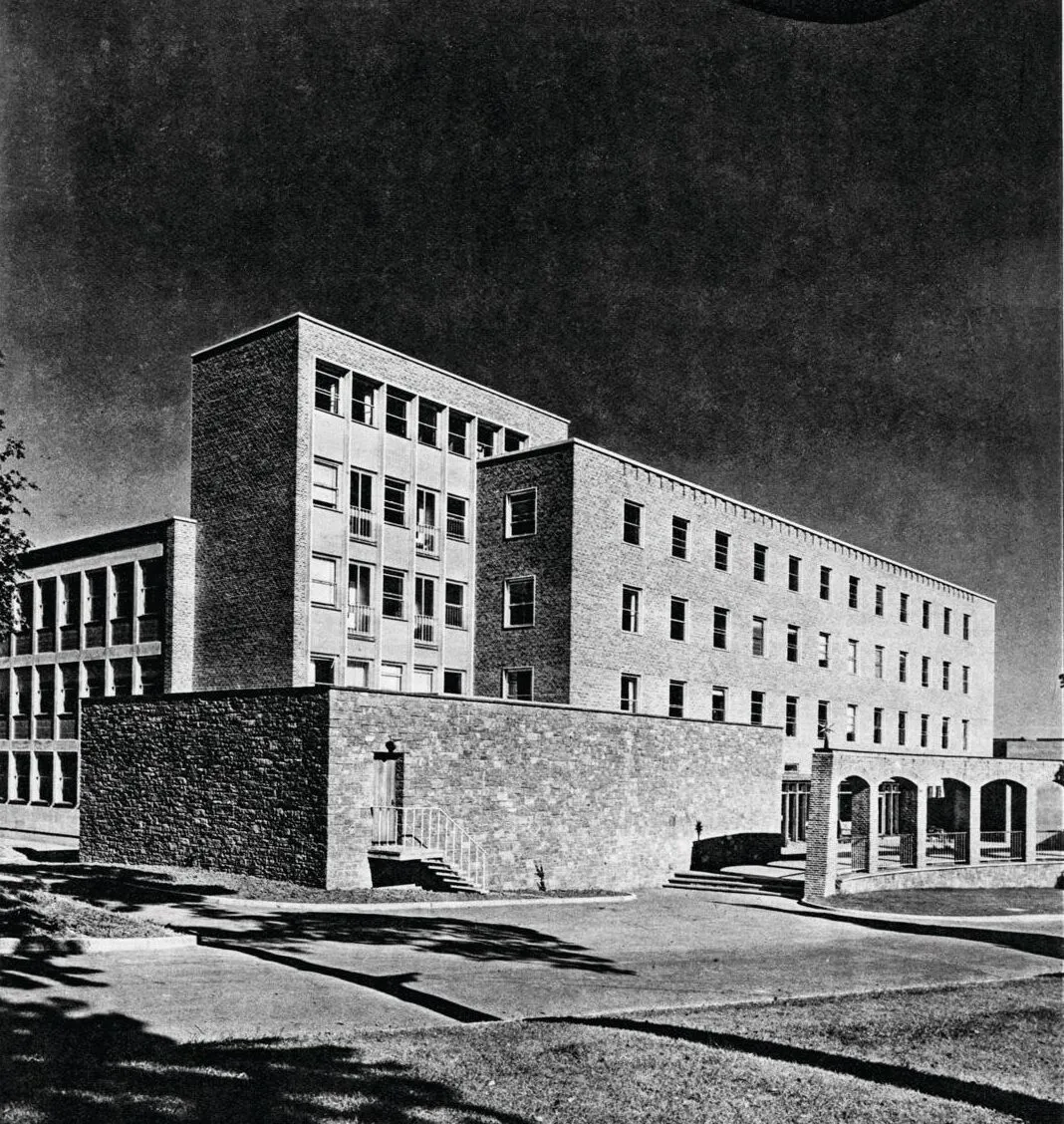

In 1926, with Braintree bursting at the seams, Francis announced plans to build an entire village around a spot he had chanced upon while out for a drive. ‘For a thousand years or more,’ he wrote in his memoir, Fifty Years of Work and Play, ‘the quiet tale of that sleepy hollow had unrolled itself with little variation until I came that day, a minister of change and revolution, to write a new chapter’. Designed by Walter Crittall and Thomas Tait, mixing Arts and Crafts-type cottages and modernism, Silver End was the concrete realisation of a utopian dream.

Not simply 600 homes replete with upstairs bathrooms and expansive gardens, but a school, playing fields, three-storey department store, a village hall containing a library and cinema, churches, hotel, allotments, farm, bakery, even its own building society and print-works for a dedicated newspaper.

Besides local people, Francis recruited workers from depressed areas across the country, as well as the disabled war veterans he housed in purpose-built bungalows. In its first decade, Silver End was claimed to be the healthiest village in England, boasting the lowest death and highest birth rates.

Curve Appeal

Crittall was soon at the forefront of a new architectural movement. If the industrial-sized beauty of the Boots D10 building and Baltic Flour Mill were among the firm’s most famous contributions to Art Deco, its most familiar lay in the curved bay windows sweeping suburbia. Having helped transform working-class housing in the 1920s, Francis’s firm was now remodelling middle-class life in the 1930s.

The family led the business for a further four decades – overseeing the opening of the first galvanising plant in Witham in 1939 and a merger with Henry Hope and Sons in 1965 – before John Francis Crittall retired in 1974. After a number of takeovers, the firm was revitalised by a 2004 management buyout and moved to a new factory in Witham. In 2010, the year Crittall won a Queen’s Award for Enterprise in International Trade, New York-based architect Juan Carretero told The Independent that ‘Crittall windows have been popping up lately in almost every new building in New York City or anywhere else in the country that might deserve the labels hip and cool’.

Russell Ager, Crittall’s MD, elaborates: ‘The windows we make today share the same DNA as the ones we made in the 20s and 30s, but we have to adapt with the times; they need to be more thermally efficient and offer greater levels of weather protection. They’re a bit like the Porsche 911 – they’ve still got that innate character and appearance, but they evolve.’

How to care for Crittall windows

- While modern Crittall windows are hot-dip galvanised, older ones are more susceptible to corrosion. You can readily remove superficial rust using a wire brush, before applying zinc primer to the frame.

- Keep frames clean and free of salt or pollution deposits by annually wiping with a mix of mild detergent and warm water, before washing off with hot water.

- Routinely inspect opening casements and weather seals, removing any accumulated paint flakes, grit, insects, etc.

- You should annually lubricate pivots and hinges (other than friction hinges), as well as check mastic and putty, replacing as necessary.