A New Leaf

Legend has it that tea was discovered by accident when in BC2737 the Chinese emperor Shen Nung saw leaves drop into the water that his servant was boiling for him to drink. At first pans were used to boil the leaves and water together, but soon wine ewers were adapted to allow the tea leaves steeping time. It was during the Ming dynasty in the 1500s that the first purpose-built teapots were made. They were made from the red-brown clay of Yixing province, which was known to be particularly heat resistant and, at first, the tea was drunk straight from the teapot’s spout.

The Portuguese Princess

The Yixing teapots first made their way to Europe tucked alongside stocks of tea imported by the Portuguese and Dutch. Though it was a known commodity in Britain (Samuel Pepys took his first sip of this ‘China drink’ in 1660) Catherine of Braganza, the Portuguese princess who married Charles II, is credited with making drinking it a fashionable pastime. She would most likely have poured tea from a Chinese stoneware teapot or a taller English silver one, much like the pots used to make coffee. Some surviving examples are inscribed with their purpose – the only way to tell them apart.

Sipping Status

After Pepys had his first cup in the 1660, little is known about serving tea until the Elers brothers arrived in Staffordshire from Holland in the 1690s and started producing replicas of the original red stoneware teapots from Yixing. Tea at the time was highly taxed and taken only in the finest households. Families such as the one pictured, painted by Richard Collins in 1727, showed their status by being depicted taking tea. The most up-to-date equipment was de rigueur. In fact, in Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey, General Tilney complains that he has only ‘quite an old [tea] set, purchased two years ago’.

Warming the Pot

The earliest British teapots were prone to cracking or exploding due to the heat of the water. ‘Which is why,’ says teapot expert Henry Sandon, ‘ladies using their best Chelsea ware would warm the pot first’. Thankfully, around 1750, Dr John Wall and an apothecary called William Davis devised a recipe using soap rock to make sturdier china. The Royal Worcester Pottery, formed in 1751, was the result. Their teapots, such as this 1756 example, quickly became bestsellers.

Brown Betty

To the delight of the British masses, the duty on tea was cut in the 1780s, even though moralists, concerned about being aped by their inferiors, claimed that the lower classes would miss out on the nutritious qualities of alcoholic drinks. As the Industrial Revolution rolled in, so did the mass production of teapots. The most famous was James Sadler’s ‘Rockingham Brown’ or ‘Brown Betty’ as it became fondly known (after its colour and the most common name for servants at the time). Sadler’s pots were thought to produce a superior brew, thanks to their shape, and by the late 1880s they were a fixture in most British households.

Careless Tea Costs Lives

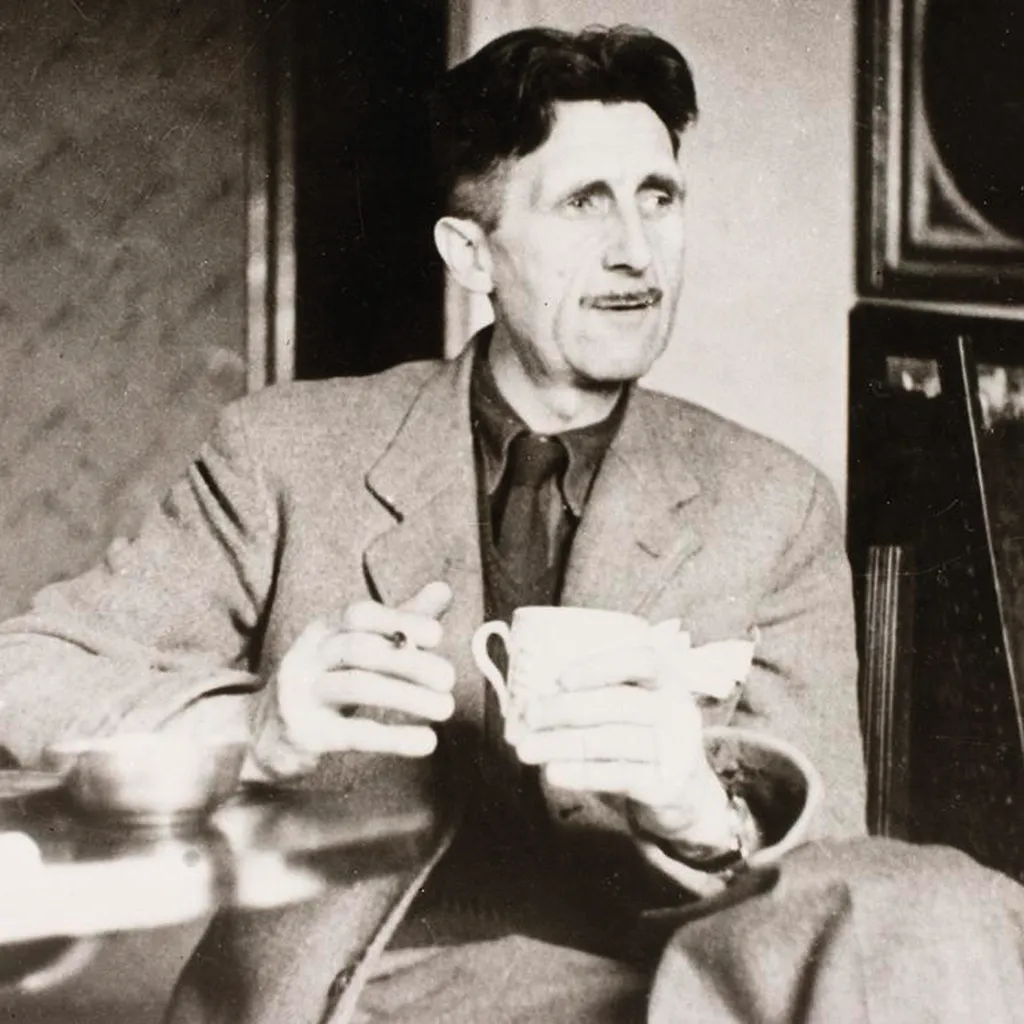

Not known for being reticent with his opinions, tea was a ritual that George Orwell turned his critical eye to in an essay for London’s Evening Standard in early 1946. He broke his ‘recipe’ down into 11 points – one of the longest of which concerned the teapot. ‘Tea should be made in small quantities,’ declared Orwell. ‘That is, in a teapot’. His preference was for china or earthenware pots, asserting that silver pots produce ‘inferior tea’ and enamel pots ‘worse’. Orwell’s favoured ceramic teapots had played a vital role in the Second World War. They were chosen by Churchill as an iconic British product and, inscribed with ‘For England And Democracy’, were shipped to America

as both pre-Pearl Harbour propaganda to encourage American involvement and as commercial products to trade for the supplies needed to fuel the UK war effort.

The Art of Teapots

The 20th century has seen the teapot become a design icon. From novelty teapots (you can own a Margaret Thatcher pot that pours tea out of her nose if you so wish) to much sought-after stoneware examples by potter Geoffrey Whiting, few ceramic objects can be found in such a range of shapes and sizes. Few people, however, have been as fascinated by the teapot’s form as Peter Shire. The American artist has said that a teapot being a sculpture and a sculpture being a teapot appeals to his sense of absurdity. He has been creating bold ceramic teapots since the early ’70s. He also says that he likes that the teapot is ‘a social modifier. It symbolises and actualises pouring out to a group of friends.’ It was Shire’s teapots that brought him to the attention of Ettore Sottsass, founder of the Memphis Group, a Milan-based design collective committed to bringing pop art’s loud tones to furniture and objects. He called Shire’s teapots ‘fresh, witty, and full of information for the future’.

A Ceremonial Cup

Readers of Memoirs of a Geisha will recall that the geisha Sayuri spends most of her formal encounters with clients pouring tea in ceremonies like the one below, captured around 1890 by Eliza Scidmore, the first female trustee of National Geographic. The Japanese rarely use a teapot in their ceremony as typically matcha tea is used, a powdered tea that’s spooned into bowls before hot water is added. The geishas seen here are pouring sencha green tea – the leaf version – which makes use of the Japanese tetsubin. This is a cast-iron pot thought to have developed during the 17th century as sencha, which requires a pot to allow the leaves to steep, became more popular. Sencha is considered a less-formal tea, more the type that is taken with family and friends.

Pineapple Mania

Originally brought to Europe by Christopher Columbus, the pineapple had become so chic and expensive by the 18th century that well-to-do partygoers were known to rent one for a night as a symbol of their wealth. The Staffordshire Potteries, by then competing with China to be the world’s centre for teapot production, were quick to catch on and thanks to Josiah Wedgwood’s perfecting of creamware (a refinement of salt-glaze earthenware that allowed for a thinner body and a more glossy finish) all sorts of bright and exotic teapots ranging from pineapples to camels began to appear. This first era of novelty teapots was also encouraged by the rediscovery of the Elers brothers’ slip-casting technique, which had been lost after they went bankrupt in 1700. Freed from the restrictions of making spherical pots on a potter’s wheel, casting allowed much more creative shapes to appear on fashionable British tea tables. The pineapple pot shown here was made in Staffordshire around 1755.

Curioser and Curioser

After her encounter with the Cheshire Cat, Alice comes upon the house of the March Hare, who is sitting outside having a tea-party with the Mad Hatter and the Dormouse. When she leaves, declaring it ‘the stupidest tea party I ever was at in all my life’, Alice turns back to see the Hatter and the Hare stuffing the Dormouse into the teapot. In Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll created one of literature’s most iconic mentions of tea. Carroll was intrigued by the Victorian’s fixation on teatime etiquette and wrote a satire of a popular book of eating manners in 1855.